Nelly Gable

Punchcutter

Conducted by Katy Nelson on July 7, 2022 at Brooklyn, New York, and Soisy-sur-Seine, France via Zoom

Gable studied steel engraving at Paris’s École Boulle, where she honed her ability to work at a minute scale. After graduation, she applied her knowledge to jewelry-making, working for eight years at MURAT, a jewelry company founded in 1848 by Charles Murat. In 1987, she was recruited to train as a punchcutter at the Cabinet des Poinçons [Punch Cabinet] of the Imprimerie Nationale [National Printing Office], becoming the first woman known to practice the discipline. Studying under Jacques Camus, Gable trained in an exacting engraving technique passed down from the storied French foundry Deberny & Peignot, where Camus himself had worked. Her training marked the beginning of a thirty-year career at the Cabinet des Poinçons, throughout which she worked on both reproducing historic punches from the Cabinet des Poinçons’s collection and translating new designs into steel. Gable not only mastered the existing Deberny & Peignot punchcutting method but also incorporated tools used in modeled engraving [gravure en modelé] to facilitate her work. By the end of her tenure, she had reached the highest rank for punchcutters within the Imprimerie Nationale.

In 2013, the Institut National des Métiers d’Art [National Institute of Crafts] of the Ministère de la Culture [Ministry of Culture] recognized Gable as a Maître d’art—the French equivalent of the title “National Living Treasure.” Hoping to bring the knowledge of the Deberny & Peignot punchcutting technique to a new generation, Gable searched for a student who could master the technique. In 2014, she began training the engraver Annie Bocel, who has also been interviewed for the Bard Graduate Center Craft, Art and Design Oral History Project. Additionally, Gable applied to include her punchcutting knowledge in France’s Inventaire National du Patrimoine Culturel Immatériel [National Inventory of Intangible Cultural Heritage], and in 2018, Gable’s application was accepted, offering a path to safeguard her knowledge of the discipline at a crucial moment in the history of the Imprimerie Nationale. Whereas in the past, government-employed typographers actively used the collection of historic typefaces for official documents, demand has shifted towards high-tech security printing for identity documents. Now under new management, the Imprimerie Nationale is known as “IN Groupe” and specializes in the production of smart cards. Its historic collection of punches has moved from Paris to Flers-en-Escrebieux in the Hauts-de-France, where a small team continues to work with the original materials.

In this interview, Gable discusses her education, her career at the Cabinet des Poinçons, the Deberny & Peignot punchcutting tradition, and the challenges of preserving craft skills.

Interview duration: 2 hours.

Katy Nelson (KN): Where did you grow up?

Nelly Gable (NG): I grew up twenty kilometers from Paris in a town called Montgeron. It was a really green commune. It’s funny because reviewing these questions really brought back my memories. Right in front of my parents’ house, there was a field with cows—something that just doesn’t exist anymore in the Paris region. And in the summer, I would go to my grandparents’ house for two-and-a-half months in the west of France. It was in the middle of the countryside, and looking back, I realize that I spent the whole summer running around outside. And now, you see, I still live twenty kilometers south of Paris, with the forest, with big trees next to me, and I can conclude that this setting is really part of my equilibrium. You see, I’ve just moved and I went back to the same thing—I mean, big trees, a river, birds, flowers.

KN: And in your childhood, what were you interested in?

NG: Standing back from everything, these questions have challenged me a little because I really hadn’t thought about all of them until now. And I realize that school had a really big influence on me. From age eleven to seventeen, I was in an experimental public school in Montgeron, and it offered a really rich education. The teachers, who I’m so thankful for now, they made us discover nature through drawing and observation. At just eleven years old, we found a lot of pleasure in learning, in studying, no matter the subject. When I was eleven, I learned broderie d’art on a big loom, I learned ceramics, and the teachers told us that it was so we’d understand materials and aesthetics. And I think it was from that moment on that I started to like drawing and develop my taste for color and beauty. So I think it all came out of the influence of those teachers when I was just eleven. We also did a lot of sports because the park was right there, so when we were psychologically tired, we could head outside.

KN: How did you eventually begin working with metal?

NG: At the Lycée de Montgeron—we call it that because it was for ages ten to eighteen—I developed my taste for the arts. And at seventeen, I wanted to take the competitive exam to enter an art school, the École Boulle. I was accepted, and so at the École Boulle, you had all these different workshops at your disposal. I wanted to be a wood sculptor, but there was too much interest in the wood sculpture workshop. We were eight seventeen-year-old students who wanted this workshop, so to decide between us, the professors said: listen, four of you are going to wood sculpture, four are going to steel sculpture. And in the end, the steel sculpture workshop, it was focused on modeled steel engraving [gravure en modelé sur acier] and engraving punches and matrices directly in steel [en taille directe]—it was a way of telling us that we were carving and we had exactly the same education as the wood sculptors. We were so young—we were seventeen. I think subconsciously, since I wanted to be a wood sculptor working at this massive scale—modeled steel engraving is so small—I always saw things magnified ten times in my head. So for me, when I was working on something, even if it was only a millimeter big, I saw it as huge, practically a monument. One day when I was engraving a letter, someone asked me what I think about when I engrave, if I think about the original punchcutter, and I instinctively said, “But I’m in Greece and here I am making a monument,” because I was making my letter. So ultimately, when I’d engrave, I’d dream of a much bigger scale.

KN: Correct me if I’m wrong, but I understand that you specialized in jewelry-making. What was it like transitioning from working with jewelry to working with type?

NG: At the École Boulle, we had courses about forty-five to fifty-four hours per week, and steel engraving—the modeled engraving that I was doing—was about twenty-five hours per week. The engraving was only done on steel. It was afterwards when I left after seven years at the École Boulle that I branched off to go into jewelry. At the École Boulle, we were trained in all the applied arts, but for me, working primarily in the engraving workshop, I was focused on medal-making.

KN: Between your time at the École Boulle and the beginning of your training at the Cabinet des Poinçons, what drew you to the discipline of punchcutting?

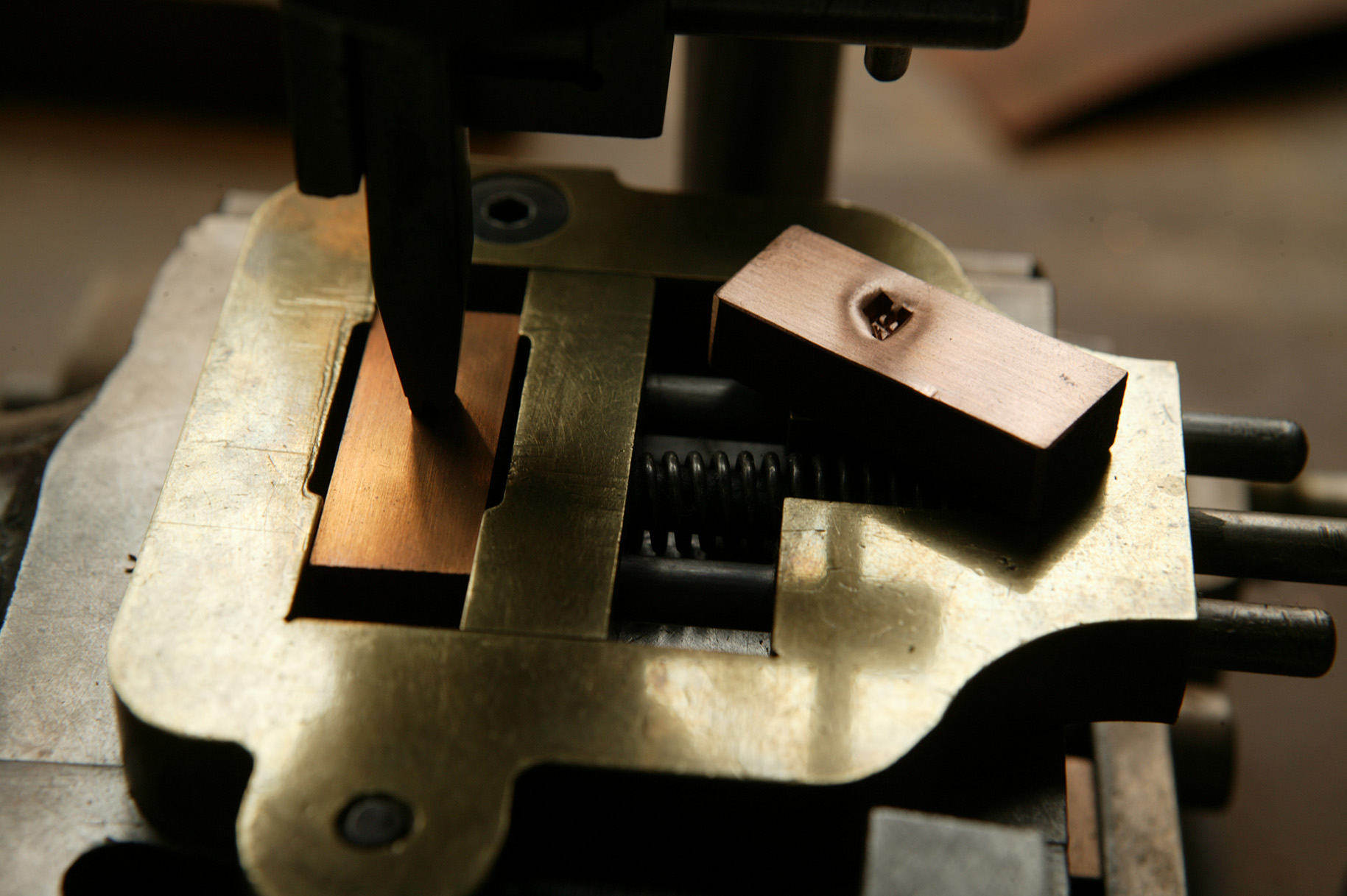

Tests for gold and copper jewelry, made from engraving punches and matrices directly in steel [en taille directe]. © Daniel Pype.

KN: The punchcutter’s workbench has a very particular design. How is it configured to aid the punchcutter’s work?

NG: The punchcutter’s workbench, with its rounded central opening, allows the punchcutter to get as close as possible to their engraving while still being able to rest their elbows and forearms. In jewelry and medal-making, we had the same wooden workbenches. However, the wooden peg installed in the middle of this niche lets us wedge in the punch for engraving because in punchcutting, the bar isn’t fixed; it’s the hand that serves as a vise since we have to turn the punch constantly. At the Cabinet des Poinçons, our workbench had three spots to accommodate three punchcutters. There have never been more than three punchcutters. For some punchcutting jobs, like cutting the Bodoni punches, self-employed punchcutters worked for the Imprimerie Nationale.

The punchcutting workshop in Flers-en-Escrebieux, France. The punchcutter’s workbench features a curved cut-out, letting the punchcutter get closer to their work than a standard rectangular tabletop. © Nelly Gable.

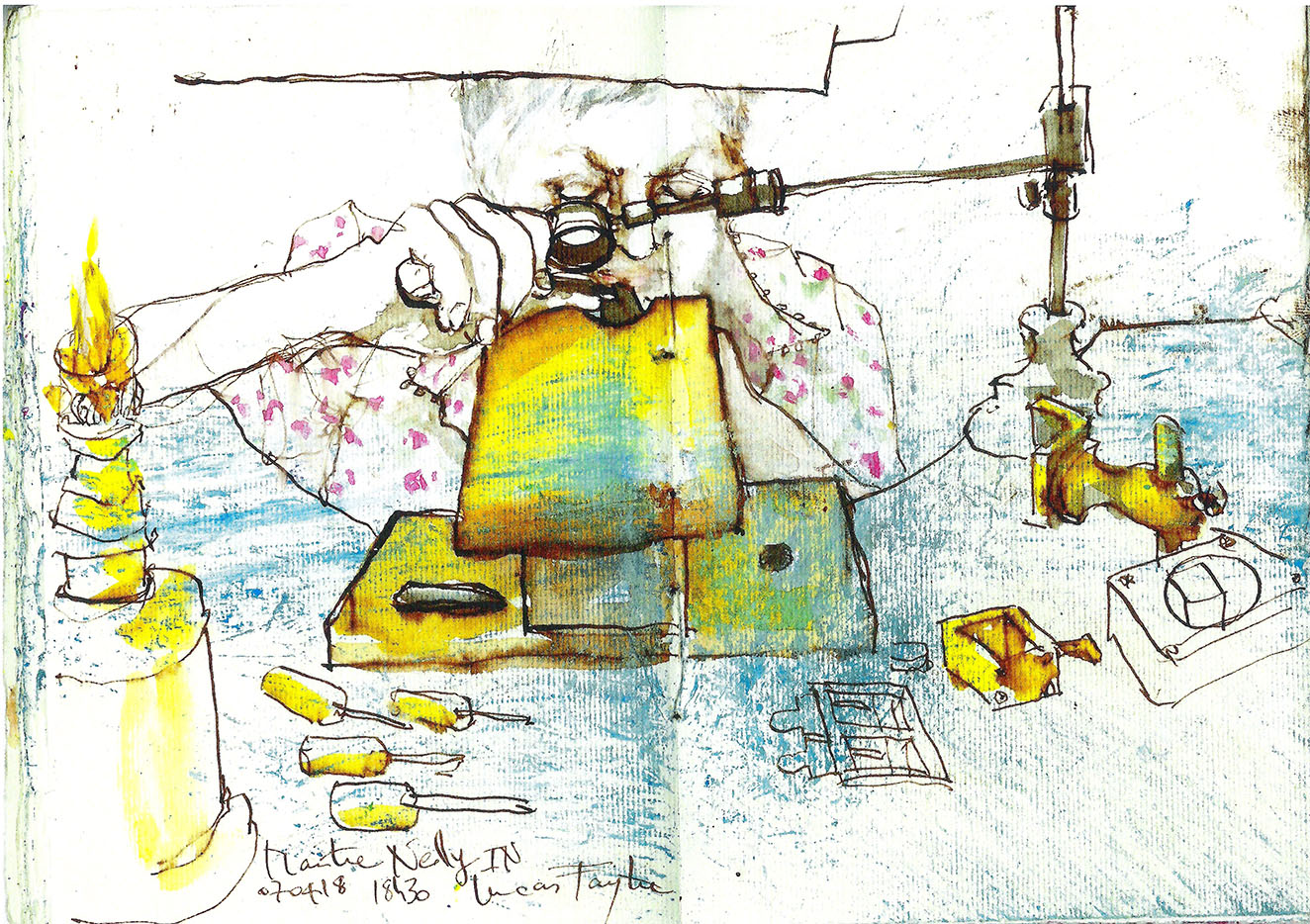

NG: My training was provided exclusively by Jacques Camus for the three years before he retired—I came in ’87, Jacques Camus left in ’90—so he was the one who did all my training. To give a little bit of his background, which I’ll explain more later, Jacques Camus started training at just fifteen years old at Deberny & Peignot—I’ll return to this foundry because it’s very important in the history of the Imprimerie Nationale—and after the foundry closed its doors in ’73, Jacques Camus joined the Imprimerie Nationale in ’75. So it was Jacques Camus who did all my training, but we had absolutely no defined program. So how did it work? We had a workbench with three curved niches. Jacques was on the right, and he started to assign me 36-point Garamond. He explained to me how it should be done, and every evening, he corrected my work. In addition, I was observing the progress of his punches to complete my training. Since I had more than twelve years of experience in engraving at this point, that enabled me to understand the steps better, because I didn’t have a curriculum for this specific training at all. So while observing the progress of his punches, I noted what was important for my own. That’s how we progressed. We started with 36-point, then we went down in point sizes and we changed families so I could work on all the historic type families. When it came to the graver—in the jewelry workshop, I worked a lot with this tool, so it came pretty naturally to me. On the other hand, when it came to the file—I didn’t know this tool very well, so I had to work incredibly hard on file exercises to get used to working with typographic punches, and on top of that, the scale of the work was getting smaller and smaller. So with hindsight, I corrected things for Annie [Bocel]. I realize that without a curriculum, it’s difficult to understand the steps of punchcutting because the typographic punch, the letter, it’s extremely rigorous. I’ve never seen such a strict form of engraving anywhere else. And the scale is tiny, so if you skip or mess up the first step—which is just the polishing of the punch—if you skip that step or don’t do it properly, you can’t end up with a good punch. So that’s why it’s important to have the curriculum so that the student can say to themselves, “Oh, no, it’s better to repeat the first step three times if I want to succeed in the end.”

KN: I’m curious to hear how the apprenticeship transitioned into the remainder of your career at the Cabinet des Poinçons, if there was an official designation when you finished, or if it was a gradual progression.

NG: First off, when you’ve done seven years of school and several years working at MURAT, do you really hope to enter the industry as an apprentice at thirty years old? You have to accept it [laughs]. It wasn’t easy either. For a year, I was in a trial period. So for that year, I made punches that were corrected by Jacques Camus and as a sort of last exam, one punch that was both reviewed by Camus and by the manager of typography of the Imprimerie Nationale. And then once I was hired on a permanent basis, at that point, I worked my way up through all the ranks of the punchcutters. That’s to say, there are five ranks of punchcutters within the Imprimerie Nationale—from lowest to highest, there’s the Troisième Catégorie [Third Category], the Deuxième Catégorie [Second Category], the Première Catégorie [First Category], the Chef Graveur [Head Punchcutter], and finally, the Hors Catégorie: Graveur/Dessinateur [literally, Outside of Category, a title that can be attained through working as a punchcutter of either existing or original designs]. You stay two years in the Troisième Catégorie and at least two years in the Deuxième Catégorie and a minimum of eight years in the Première Catégorie. There’s no guarantee of progressing beyond the Première Catégorie to become a Chef Graveur—you might stay in the Première Catégorie your whole career. The titles of Chef Graveur and Hors Catégorie have to be awarded directly by the Director of the Imprimerie Nationale. So that’s how you climb the ladder of punchcutters.

KN: Did you develop particular interests or specializations as you climbed the ladder at the Cabinet des Poinçons?

NG: Since I came from the applied arts, I lacked some of the training of those who came out of the École Estienne. So I took a lot of courses in Latin calligraphy, Arabic calligraphy, Chinese calligraphy, to teach myself [pause] to perfect my eye for drawing different scripts. And when I had a Japanese character to work on, I could understand the shapes. So I had my week of work and I completed by evening calligraphy classes not to have a perfect education but to deepen my knowledge. After that, I also deepened my knowledge of the history of the punch collection.

KN: What projects have you been most interested in over the years?

NG: Ah, the one that I remember the most distinctly is the reproduction of the typeface Luce! Reproducing this typeface’s ct ligature and ampersand was pure joy. Over three weeks, I engraved a tiny vignette of this typeface with all its imperfections. Also, the engraving of the Euro sign, which gave rise to a film that’ll be put on the site of the Patrimoine Culturel Immatériel [Intangible Cultural Heritage]. I also had many interesting projects related to typography, apart from punchcutting, like the project La collection des Bois gravés du XXe siècle [Collection of Engraved Woods of the 20th Century] and the sculpture Haute voltige des signes [High-wire Acts of Signs], which I made for the show Révélations at the Grand Palais in Paris in 2015. In short, I feel that all my projects were interesting!

Left: Gable’s annotations on a Euro symbol designed by Frank Jalleau. Jalleau’s Euro symbol was ultimately adapted for all of the Imprimerie Nationale’s typefaces. Right: A finished 14-point punch measures just three millimeters high. © Daniel Pype.

In addition to reproducing historical punches, Gable collaborates with typeface designers to translate new designs into steel. Here, Gable’s punches, smoke proofs, and matrices for designer Frank Jalleau’s typeface Francesco sit atop a marked-up print-out of Jalleau’s design for a lowercase m. © Daniel Pype.

But I’d like to come back to the work of reproducing old punches, which amounts to about eighty percent of our work: if there was a broken punch, we couldn’t make a matrix from it, and so we couldn’t make lead type. So our job was to make a new punch. In terms of the old punches, the punchcutters of the Cabinet des Poinçons felt an ethical obligation to make identical copies, that’s to say that if the punchcutter had originally made what we call imperfections or defects, it was absolutely necessary to remake them identically, and that really required having a number of years of experience because the defects had to be positioned at exactly the right place. Knowing that we’re constantly turning the punch, we had to avoid amplifying the defects. Adding to the challenge, you have to understand that this was all at a very small scale. So this was the final phase that required the most experience and judgment. In other trades, you might also make punches, but this was really about making reproduction punches. I have a little anecdote: I was working on a lowercase x with a small body, and when we work, the letter is upside down and we keep on turning the punch as we work on the letter. This x had a defect at the top of a contour, and in the end, because I was turning it and the x looks similar on both sides, I made the defect at the bottom. We could have passed it by, saying nobody will see it except my colleagues, but the ethics are to redo it identically. So I had to abandon that punch entirely, and then I went for a walk and came back and a few days later I started it all over again. You see, that’s it right there. Why do that? The punches of the Imprimerie Nationale are really what I call excellence. It’s because this work of reproduction is so perfect.

KN: I’m curious to hear where this idea comes from of viewing the punch as an artifact that needs to be preserved precisely, as opposed to as a representation of an intended design.

14-point reproduction punches for the typeface Luce, named after its original designer and punchcutter Louis-René Luce. When reproducing historic punches, the punchcutters of the Imprimerie Nationale were careful to recreate every detail—even imperfections—so that replacement characters would be indistinguishable in print. © Daniel Pype.

KN: Can you tell me what a typical day in the Cabinet des Poinçons would have been like?

NG: So the hours were from 8:00 AM to 5:00 PM. The Cabinet des Poinçons—as I knew it because we moved several times—was on the third floor, very close to the management, very close to the Director, and that’s one of the reasons why the punchcutters were always very well dressed because at any time the Director of the Imprimerie Nationale could come with a guest, an ambassador or someone else, to the Cabinet des Poinçons. Jacques Camus, who was the Chef Graveur, would lead visits like that. So we’d arrive early, around 8:00 AM, set up at our workbench, and work all day. We took a few breaks, but it was eight hours of punchcutting, and to rest our eyes, we’d look out the window. The library of rare books was next to us, so I was often told to go into the library and look at books to rest my hands, my arms, my eyes, everything. It was very quiet—that’s what surprised me at first. You could hear the sound of the file, you see, it went [mimics sound of a thump, thump, thump followed by a scrape, scrape, scrape]. And Jacques Camus, he worked a lot with the radio, so you could hear the radio. There was the smoke and then the noise of the tools. And we worked with steel, there were no machines, so it was very calm. It was just the three of us, so the workbench had three places and we each had our own tool set, so we worked with our own tools. One little thing that was unique to the Cabinet des Poinçons—it’s funny, looking back on it—we were outside of the factory areas, the ateliers. That’s to say that when you’d come to work and stay eight hours in the Cabinet des Poinçons, you’d have no contact with the other ateliers or the other workers outside of the management—the Cabinet des Poincons even had a gated entrance with a code. We were on the hushed side. When you arrive in a company, usually you observe a lot, but for several years, I didn’t go down into the ateliers because the punchcutters didn’t go down there.

Working at such a small scale took its toll on the punchcutters of the Cabinet des Poinçons. Gable would rest her eyes by looking out the window or visiting the adjacent library. © Daniel Pype.

NG: Yes, I mean, the punchcutters engrave their punches and their work stopped at that level. That’s to say that to strike the matrices, a typefounder might have gone up to the punchcutter to get the punch, but the punchcutter never struck their own matrices. It just wasn’t done. You see, it’s kind of like the French expression, you don’t mix dishtowels with napkins—I don’t know if that exists in English [laughs], but that’s kind of it. The punchcutters worked close to the management and so they would wear suits, while in the ateliers, they would wear real workshop attire—a uniform of grey jumpsuits emblazoned with the text “Imprimerie Nationale.” When I was working in jewelry, I made my own punches, I made my own matrices. And so, for me, when you’re in a trade, I think it’s important to know what happens upstream and downstream from you. And it really bothered me that I couldn’t go down to the ateliers and see the before and after stages. So that’s why as soon as I was able to have a little more freedom, more experience—more years and more freedom—I started to want to explore the ateliers, and then I started to make my own matrices, especially since the typefounder who made the matrices had retired. To strike matrices, which is its own really specific skill, I asked management if I could be trained for nine months, so I asked a former Foucher typefounder to go into his old atelier at the Imprimerie Nationale so that he could teach me the subtleties of striking large punches, small punches, accented punches. And I passed all of that knowledge on to Annie. At the same time, I also learned about electrolysis in another atelier outside the Imprimerie Nationale, because I had noticed that in our collections, there were many matrices made by electrolysis, and when we had visitors, we didn’t always know how to explain electrolysis, or only very, very vaguely. So I thought that to be able to explain it without it all being hazy [laughs] we had to experiment with it, so I experimented with all that, which to me is crucial to understanding punchcutting in its entirety. When you look at the old punchcutters, some of them drew their type, they engraved, they struck their matrices, they founded their lead type, they printed. So that seemed logical to me, even if at the Imprimerie Nationale, all the trades were compartmentalized.

KN: Can you tell me more about the challenges of ensuring continuity in the full chain of type production?

NG: Despite all the changes in the printing world that accelerated in the seventies and eighties with the arrival of photocomposition and then desktop publishing in the nineties, the Imprimerie Nationale had managed to keep its entire graphic chain with punchcutters, Monotype and Foucher typefounders, and typographers who still composed our historical typefaces by hand. But the situation really started to deteriorate in the 2000s, when the last Foucher typefounder retired without training a replacement. The workshop is still surviving off its old stock of lead type. It’s important to know that in order to make lead type of our historical typefaces, the only casting technique is the one issued from the Foucher foundry. In order to help us to recover this technique, Rainer Gestenberg, the last founder of Stempel who was still producing lead type until December 2021 in the Haus für Industriekultur [House of Industrial Heritage] in Darmstadt, Germany, came to train our founder Philippe Mérille with the invaluable help of Philipp Rehage as translator.

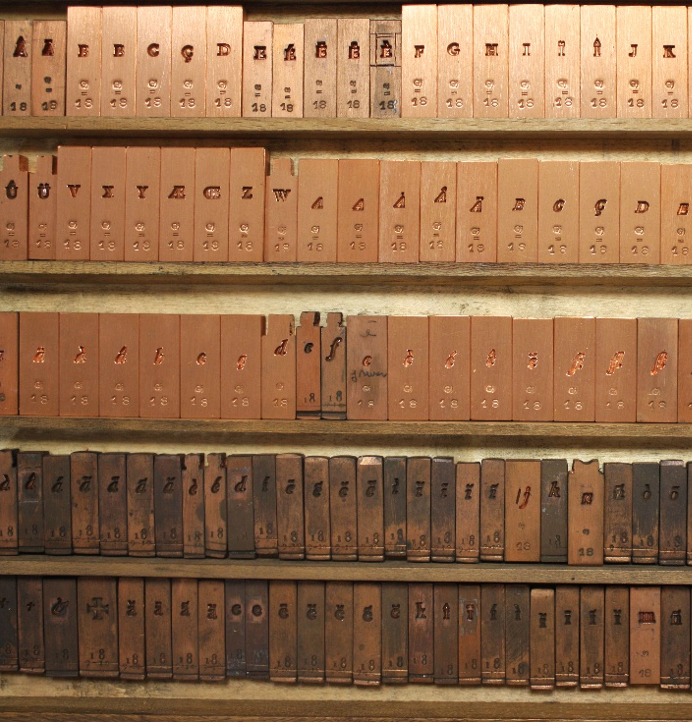

Rows of matrices. Punchcutting is not the only step of typographic production at risk of disappearing; today, typefounding remains an equally rare skill. © Daniel Pype.

KN: The typographic chain depends not only on these skilled individuals who are trained in different steps of the process, but also on the existence of very specific tools. I’m curious to hear about the challenges of preserving the tools themselves.

NG: In terms of the tools, traditionally, tools were passed down from punchcutter to punchcutter. As soon as a punchcutter retired or stopped working, he would graciously give his tools to a young punchcutter. Working on engraving punches, we use really specific tools. So what I was able to observe when, for example, Louis Gauthier came to the workshop in 1948—he came from Deberny & Peignot—he came with his tools. As did I when I came from my old company—I came with my tools, with my gravers and everything. So Louis Gauthier came with his tools to the Imprimerie Nationale, and when he retired, he actually took his tools back, and so we only have photos of them. And by doing a little research, I realized that by looking on the workbench, there were some tools that never reached us. They disappeared—they must be with Louis Gauthier’s family somewhere. So when I arrived, what I did on a personal basis and continue to do is I scanned all the tools next to a ruler for scale—the small simple tools, like the T-squares and the T-squares for oblique lines—I scanned them all so that later we could see what different T-squares the punchcutters used. For the more complicated tools, I’d bring them home. I have a friend who’s an architect and he scanned all these tools in 3D, and we’re currently making a 3D file. It’ll be given to the Ministère de la Culture [Ministry of Culture] in the fall of 2022 to be incorporated into the record of Patrimoine Culturel Immatériel. Now that I’m outside of the Imprimerie Nationale, I can afford to say this: access to the Imprimerie Nationale is exceedingly difficult, and even more so now with our new management [IN Groupe]. For me, it was unacceptable that people from all over the world couldn’t have access to these tools if they wanted to recreate them. So by adding this file to France’s Patrimoine Culturel Immatériel, it’s free and accessible to all. That’s what I did to safeguard the tools.

By creating scanned images of punchcutting tools, Gable hopes to democratize access to these specialized implements. © Nelly Gable.

NG: I think a lot has changed. For example, I’m a Maître d’art, and this year, I was part of the jury to nominate the new Maîtres d’art—every two or three years, there are people with very rare trades that apply. It’s a process that’s managed by the Ministère de la Culture. You realize that there have been so many trades that have disappeared forever—that are no longer here and that won’t ever come back—and you realize that to counteract this phenomenon, the older generations now want to train young people by offering them all their knowledge. I believe that this has changed a lot. Before, it was, as you say, secretive and by word of mouth. But a lot of things have been lost and that’s unacceptable. I think that now we’re aware of it, and, you see, to answer your question, that’s why in France, there’s this program of the Maîtres d’Art et de leurs Élèves [National Living Treasures and their Students]. It’s managed by the Institut National des Metiers d’Art which is part of the Ministère de la Culture and which is specific to France. There’s no other [pause] we’re envied in Europe for this system. And who’s taking on the responsibility so these professions can be taken up again by young people? To share a little story: I was at the Imprimerie Nationale, I was working on the Didone family and also on the Marcellin Legrand, and it’s a very strict typeface, with right angles, and it was very difficult to render the angles well at that scale without what we call “talonner” on each side—damaging the edges of the character by accident while you’re engraving. I had been at the Imprimerie Nationale for ten years. And Michel Portron, whom I had replaced, came and said to me, "So Nelly, how are your Didot angles going?” I said, “I’m having trouble, I’m damaging them.” He said to me, “But do you know about sharpening Didot gravers?” So I said, “No, I don’t.” “Well, it took ten years for me to be shown, so I waited ten years to show you.” So you see, with a model like that, I think I could never have taught Annie. Instead of bothering for so many years doing these angles with normal gravers, I could have just learned this simplified sharpening technique. But then again, I’m lucky that he did show it to me. He was able to do it very well, too. He showed me, and he offered me three gravers sharpened this way. You see, it’s just a little anecdote.

Certain sharpening techniques can make it easier to tackle challenging shapes, like the right angles found in Didone typefaces, but such tricks of the trade were often closely guarded—a practice Gable hopes to change by sharing her knowledge openly with students. © Daniel Pype.

NG: So I won’t tell you everything, because it can be quite unpleasant [laughs]. But here’s what you have to understand: it’s a totally male profession. The main art schools, like the École Boulle and the École Estienne, only opened their doors to women after 1968. So before, young girls couldn’t access an apprenticeship in this profession. Like me, I was the class of ’73 at the École Boulle. I was the fourth class of women and one out of four engravers. At the Monnaie de Paris, the first class with women was in ’72. And so it was rare, but we were the first because these professions weren’t open to women before. There’s a little story that amused me a lot when I was in the jewelry business: I was also the first woman to be a modeled steel engraver, and all the engravers—I think we were five engravers—and the toolmakers had been summoned by the CEO, who told them, “Watch your language, we’re going to have a woman engraver.” So they had a little lecture in morals. And in terms of the Imprimerie Nationale, there, that was more complicated because it’s a completely male and macho world. And they’d often use complex puns and jokes—always below the belt—and it wasn’t always very pleasant. So I said to myself that I had to move forward. I mustn’t stop because of these trivial things, and I told myself that to succeed as a woman, I had to be one of the best. I think I was a fighter, and I advanced without aggressiveness. I’d say to myself, “Let’s leave all that aside,” but I admit that it wasn’t very easy. Once, I went to bring some pieces from the Cabinet des Poinçons to a museum, and I waited for a really long time at the reception. Ultimately, I showed up and they said, “Ah, but they were waiting for a gentleman with a mustache.” I said, “Sorry, I don’t have a mustache, I have a skirt.” You see, these were small things, but you have to put this in context—it was twenty years ago now. I think a lot of professions have become more feminized and there are fewer problems. We were really one of the first generations to enter these very male-dominated trades, and I always got a kick out of wearing a dress or skirt to say I was a female punchcutter [laughs] that was just me amusing myself. On the other hand, throughout my career as a punchcutter, I’ve heard the sound “graveur,” “graveur,” and I never wanted that name to be feminized. Because the men of the Imprimerie Nationale would deform “graveuse” into “graveleuse.” So in some books they change it to “graveuse,” but whenever I have a say, I leave “graveur” because it corresponds to the sound that I associate with my profession. Even if some disagree with me. [“Graveur” is the masculine form of “engraver” or “punchcutter,” “graveuse” is the feminine form, and “graveleuse” is a derogatory word.]

KN: Zooming out a bit and thinking about punchcutting within France at large: what distinguishes the French punchcutting tradition from punchcutting techniques practiced elsewhere?

The Deberny & Peignot punchcutting technique was passed on from punchcutter to punchcutter. Here, punches stamped with the names of their engravers constitute a sort of directory of the Cabinet des Poinçons. © Nelly Gable.

An in-progress R and a completed R. To create the negative spaces within a character—otherwise known as counters—Gable works by hand with a graver, carefully following a stippled outline. © Nelly Gable.

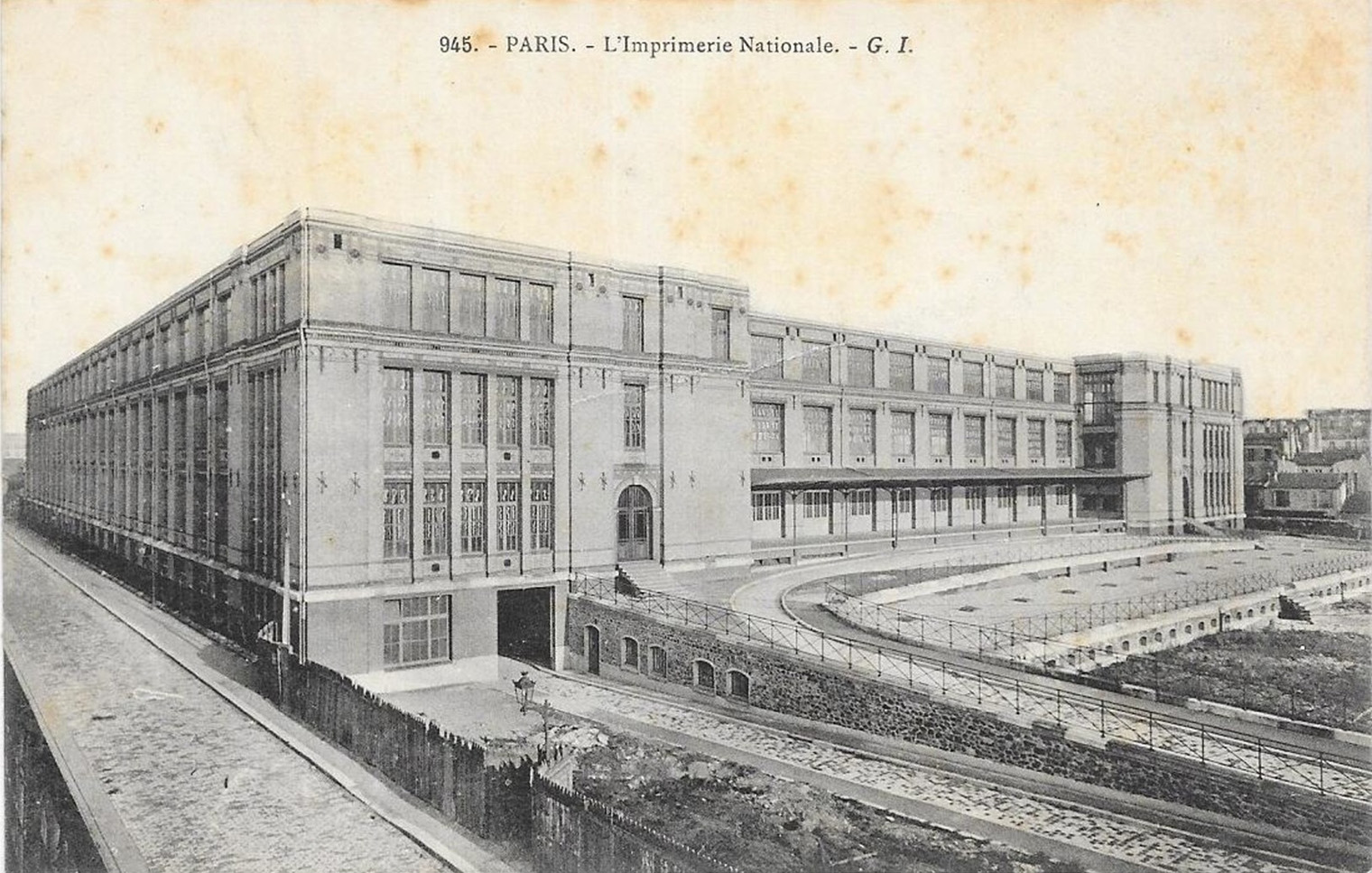

NG: You have to understand that at the level of the Imprimerie Nationale—it was originally called the Imprimerie Royale, then the Imprimerie Impériale, and then the Imprimerie Nationale—from the beginning, there were punchcutters who worked for it. That’s how we know all its great typefaces—the Grandjean, the Luce, the Didot, the Marcellin Legrand—we know all these great typefaces by the names of their punchcutters. Afterwards, when it became national, it was still a printing house and had the exclusive role of producing all the administrative printed matter. So there were a lot of people involved, and for example, certain administrative printed matter was composed in lead type with the historical typefaces, like the Marcellin Legrand, so that’s why the punchcutters had a lot of reproduction work, because there were big requests from the typographers, who were at least 300 people. From the ’80s onwards, the Imprimerie Nationale really suffered with the loss of the exclusive right to publish official documents for all the various administrations of the government. So there were fewer jobs, and actually, when I entered in ’87, there was still research into creating new typefaces—there was the Atelier Nationale de Création Typographique [National Workshop of Typographic Creation], which was within the Imprimerie Nationale and housed designers and students. So there was still a community focused on type design. But then the Imprimerie Nationale really entered difficult times, and stopped housing the Atelier Nationale de Création Typographique, which is now based in Nancy and has become the Atelier Nationale de Recherche Typographique [National Workshop of Typographic Research]. Now we’re no longer called Imprimerie Nationale but “IN Groupe,” and we’ve become the leader in security printing for identity documents. The union advocated to preserve that exclusive right to print identity documents so that more jobs could survive. So in terms of the great Imprimerie Nationale as we knew it, with the typographic work that we knew [pause] you see, now only the Atelier du Livre d’Art et de l’Estampe [Workshop of Book Art and Printmaking] remains. There are hardly any printing machines left at the center of IN Groupe. The only things left have been safeguarded—this is an unheard of opportunity for the heritage of the printing—I mean, after our move from Paris, we moved into storage buildings, and otherwise the entire collection of punches and matrices is based in the north of France, in the Hauts-de-France. And there’s a small workshop, the Atelier du Livre d’Art et de l’Estampe, with about ten people who continue to work with the old machines and who continue to carry on the manual composition of lead type from our historical collection. Those people can really be considered the conservators of the former Imprimerie Nationale.

From 1903 to 2004, the Imprimerie Nationale was housed in Paris at 27 rue de la Convention. Now, under the management of IN Groupe, the historical collection is kept in the Hauts-de-France. This image is reproduced under a CC-BY-NC-SA 2.0 Creative Commons license.

NG: When we had all these great difficulties at the Imprimerie Nationale, I felt that punchcutting was going to disappear since I was the only punchcutter left in the Imprimerie Nationale. My colleague Christian Paput had left—he took a redundancy plan in 2005—so I looked around to try to figure out how I could help the craft. In my case, without really knowing what the Imprimerie Nationale wanted, I knew that they were in great difficulty, so I understood that asking to train a punchcutter and telling them that it would take five or ten years was not really going to be accepted. I knew of the Maître d’art program, and I decided to apply for the title of Maître d’art by submitting a file demonstrating the value and importance of this know-how and containing photos of some of my work. I was accepted, which was a great opportunity. And so Annie applied as my student, and now being appointed by the Ministère de la Culture meant that I had more leverage within the Imprimerie Nationale to say that we should train a punchcutter. So that gave me more leverage to free up my time and to take on training Annie. And to come back to the Patrimoine Culturel Immatériel: it was of my own accord that I put together the file to present to the jury in charge of the Inventaire National de Patrimoine Culturel Immatériel to add punchcutting to the inventory and safeguard this knowledge, because I saw that in terms of the Imprimerie Nationale, there wasn’t a willingness to save this expertise. So I wanted all this know-how to be made available as a public asset to the community, so I said to myself that I was going to present myself and see if my file would be accepted. I was lucky too. My application was accepted, and I’m still adding to the file with new elements. But to answer, in short, it allowed me, as just this small person Nelly Gable within the Imprimerie Nationale of the IN Groupe, to have a certain stature because I had the Ministère de la Culture behind me. And you see, when a few months ago I was on the jury of the future Maîtres d’art, there was a file for the Chalcographie du Louvre, which is also part of the Ministère de la Culture. The printers and engravers asked to be Maîtres d’art to be heard by their institution too. I had to defend this file—I related to their cases and understood why they applied, because I was Nelly Gable, an engraver in a huge institution, and I know how difficult it is to make your voice heard. So you see, we may be part of a big institution that had typographic influence at a certain point in time, but that’s no longer the priority of IN Groupe. So fortunately, we have the means to [pause] I’m not going to say to defend ourselves, but to save the know-how for future generations. And for example, at the Imprimerie Nationale, since it’s a large group, just to talk to you, I would have had to ask for authorization and I would have been asked for the minutes. That’s to say that a lot of things couldn’t be done when we were at the Imprimerie Nationale because there was a huge veto at the level of our communications department. And that’s why I said to myself that since there were going to be more and more vetoes, we had to open up our know-how. And now I’m free to open it up however I want.

KN: These designations within France, are they changing the avenues of economic support that exist for the discipline?

NG: At the level of the Maîtres d’art, in general, the Ministère de la Culture grants the Maître d’art’s workshop a subsidy for three years to help support either the student’s travels or the purchase of teaching materials. The Imprimerie Nationale was rich at that time—they didn’t have a subsidy, but they still supported Annie and for that I thank them. I mean, we were able to do a lot—she was able to come to the United States and train with Stan Nelson, she was able to see Richard Årlin in Sweden because within the Ministère de la Culture, there are foundations that provide funding. So we had asked for funding for the trips and for the book that we made together [Drawing the Movement: Cutting the Type Punch]—we didn’t do those things through the Imprimerie Nationale. We did them with funding from the Bettencourt Schueller Foundation. So there is financial assistance that the Ministère offers workshops, and there’s assistance from two patrons like the Foundation for very particular things, so those are the options. But on the other hand, for example Annie, who now has her own workshop, she doesn’t get any help from the Ministère anymore. She has to get by on her own. But there’s an independent association called the Association des Ateliers des Maîtres d’art et de leurs Elèves [Association of the Workshops of the Maîtres d’art and Their Students], and I’m their treasurer. We also have patrons—the Ministère de la Culture is one patron, and they do have some oversight in how funds are used, but there are also other donors who provide funds without stipulations. In a case where a Maître d’art or a student has trouble buying materials or other things, we free up funds for them and ask our patrons to help. Annie got funding to buy a printing press. It’s a case by case basis, but we have volunteer associations that make sure to look for patrons to help them. And we help the Maîtres d’art and their students start putting on exhibitions in big places in Japan, Venice, Paris—the Salon Révélations, the Salon du Patrimoine [Salon International du Patrimoine Culturel]. That is to say that behind the scenes, we help students and Maîtres d’art exhibit their pieces.

KN: And in the case of working with Annie Bocel, I understand that you worked together for several years in a one-on-one apprenticeship. Are there other avenues for learning punchcutting outside of the apprenticeship model?

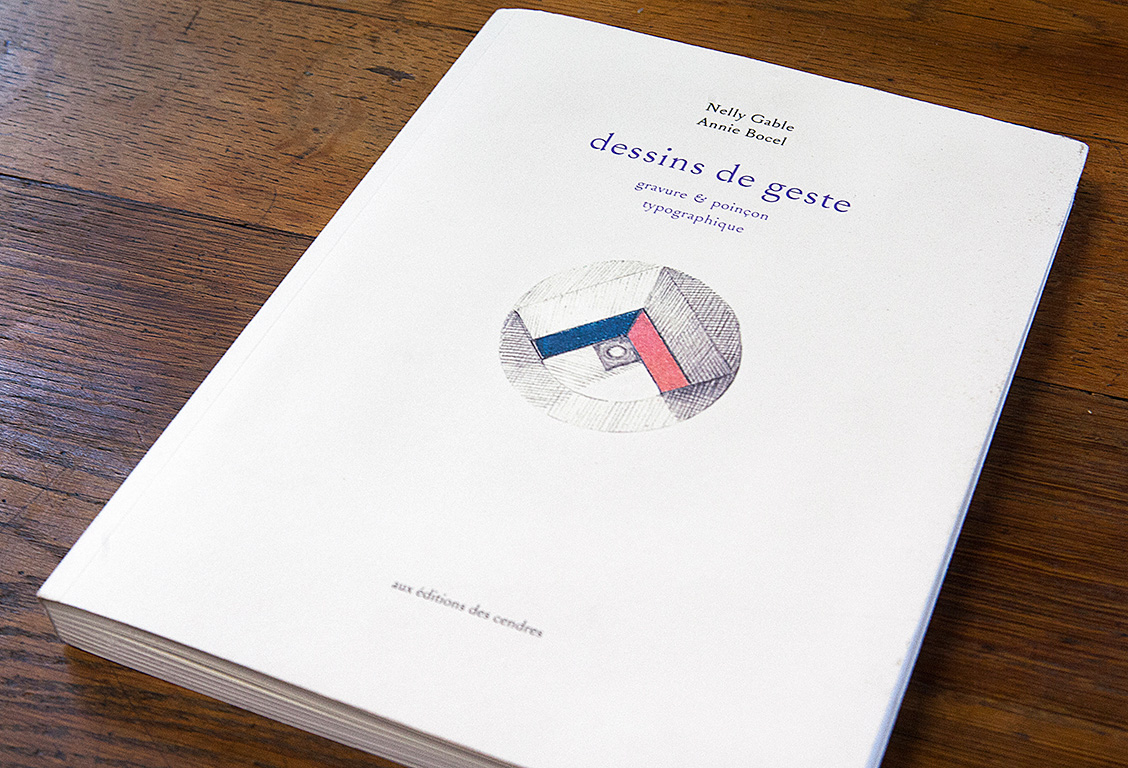

Nelly Gable and Annie Bocel published Dessins de geste: gravure & poinçon typographique [Drawing the Movement: Cutting the Type Punch] in 2019 to open up their knowledge of punchcutting to new practitioners. © Daniel Pype.

KN: And a closing question: how do you hope your students will use their knowledge of the craft?

NG: Look, I really have no restrictions, no restrictions at all. The only thing that mattered to me was to make this craft known, so that type designers, scholars, researchers can appreciate the quality of the work when they see a punch. You see, one day, we had a visit and a high-up director took a punch out of a box, and he threw it like this on the box [makes throwing gesture]. He ended up damaging ten punches. So that’s unacceptable. But he was one of our directors. And I thought, never, this can’t be the way it is. That’s why by explaining this craft, by offering books, even those who aren’t practitioners will have a respect for the old punchcutters and will say, “Wow, the four-point or the eight-point Didot, but that’s wonderful!” That’s what’s important. I think it’s that respect for the work of the old punchcutters. So without any restrictions for the new generation—I hope they go wild with creativity. That’s my wish for them.

[End of interview]