Kate Sekules

Mender, Mending Educator and Costume Historian

Conducted by Mary Adeogun on April 15, 2021 at New York, New York via Zoom

Sekules pivoted to academia after seeing the need for scholarly research in mending. Since 2020 she has been pursuing a PhD in decorative arts, design history and material culture at the Bard Graduate Center. Her dissertation topic is the history and taxonomy of mending. Sekules has led workshops and given lectures at New York University, Parsons School of Design, the Fashion Institute of Technology, the Textile Arts Center, RISD Museum, Columbia University Chicago, the Costume Society of America, the Textile Society of America, the UK Association of Dress Historians, Winterthur Museum, and other venues. Her work on mending and repair has appeared in publications such as Harper’s Bazaar, The New Yorker, The Guardian, and the New York Times. She has continued to champion buying vintage and visible mending as a way to extend the lives and stories of clothes. She is part of an extensive community of menders, vintage fans, textile artists, and fashionistas, and stays connected through social media, @visiblemend on Instagram.

In this interview, Sekules talks about her meditational, daily mending practice, and how she learned and developed the techniques that have become part of her mending taxonomy. She discusses terms like menditation, patchiko, endoskeleton, invisible mending, and visible mending, and breaks down where they originated from and the complicated cultural and social realities behind them. She recalls how “Make do and mend” was built into her upbringing by immigrant parents who lived through the scarcity of World War II. Sekules also speaks about her experience on the business side of fashion. Finally, she talks about the power of the needle to address social injustice.

Interview duration: 47:30 minutes

Kate Sekules (KS): Hi, Mary. I'm Kate Sekules and I am a mender. I'm a mending educator, which is an informal self-administered title because mending is—as an ontology, as we say at BGC [Bard Graduate Center]—very much developing. There is no such thing as a professional mender, but there is beginning to be. And that's one thing that I'm very focused on helping into the world. So I've been mending all my life informally. And in the last few years it's been getting more and more organized. It's at the level now of certainly craft. And whether it's an art is up for debate. But I always describe the kind of mending I do, which is visible mending, as more art than Etsy. It's a kind of scrappy art form. But I'm a PhD student, as you know, at BGC. So my dissertation subject is mending. [laughs.] And I am in the process of constructing a taxonomy of mending and using that to connect a lot of dots together, so that mending becomes a subject unto itself and something worth studying in its own right and also worth collecting in the museum and also in person. I mean, personally, I feel that mends—and mostly I'm talking textile—can be valued as objects more than they currently are, which is very little, but that's also changing. That was a bit rambling, but, I'm a mender, if you want one word.

MA: Perfect. Let's start by doing a day in the life. I know everyone hates this question because, especially for makers, it's like, what day? There's no consistent day, but I just want to kind of get at, you know, if you could tell us about how you allocate your time and your energy on different things.

KS: Oh, yeah, no, you're totally right. Every day is utterly different, which is how I like it. Right now I do a lot more academic work than mend—no, I wouldn't say more than mending. The thing is about mending, physically mending—I have all these puns. I'm afraid you're going to have to get used to the puns, and one of them is menditation. And as someone who practices that kind of—I don't want to call it mindfulness, because I hate that word. It’s mindlessness. You want to get out of your mind, not into it. But anyway, menditation is real. I do find that mending as a practice is centering, and it's good for the soul. And it's good to get into your hands and out of your head. So I do mend every day. I said that in relation to doing more academic work. You know how overwhelming it can be, the workload in academia. So there are times when I do a lot more of that. So I write about it, think about it, read about it, write about it, as I said, I do it. Mending is such an old, old—possibly the oldest—form of human endeavor. One of the most fundamental things that humans have always done. And when I say humans, I mean women. [chuckles.] When I say women, I don't mean it's only been women ever, but it is one of those invisible forms of labor that has sort of held up the structure of the wardrobe of the people, but also of human life. We haven’t been able to—we would not have been able to construct a civilization without having forms of repair. And when it's about the clothing particularly it's emotional, physical labor. But it's also—well, nowadays it's rewarding. So I feel that curating a wardrobe and then curating again—not a great word—but curating wardrobe is the bigger part of where the mending fits. And I love, love, love clothes. 'Cause I am a costume historian. That's how I came to this. And before that, my whole life, I was a—now they call it—vintage collector. But, as you know from the book, I've been an old clothes fan my entire life. So I feel that—I'm really rambling, but anyway—collecting old clothes and mending them is a fundamental thing that I do every single day. So now that we don't go out I don't get dressed so often. [chuckles.] but I do still care for what's in the closet. So, I've [laughs.] not at all answered your question, but every day has some parts of all of these things in it. Certainly reading and writing, certainly mending and curating clothes and thinking about wardrobe and the stories in our wardrobes—that's what came first for me, before anything else. Understanding that clothes have a narrative and that this is important and that this is really a valuable thing to—it used to be taken for granted or not noticed, and now I think more and more, we are understanding how it has a place in not just our personal lives, but in history.

MA: And you absolutely answered my questions. [laughs.] I want to dive deeper into something that you said. You mentioned mendfulness. I noticed that specific terminology that you use in the book MEND!, and then also in the Instagram engagement that you do. And I would love to understand, in those moments where you're caring for your closet, especially now in the pandemic, what is your process like? How do you decide what you're going to work on today? What does that mendfulness process feel like for you as you're like moving through it, mending something?

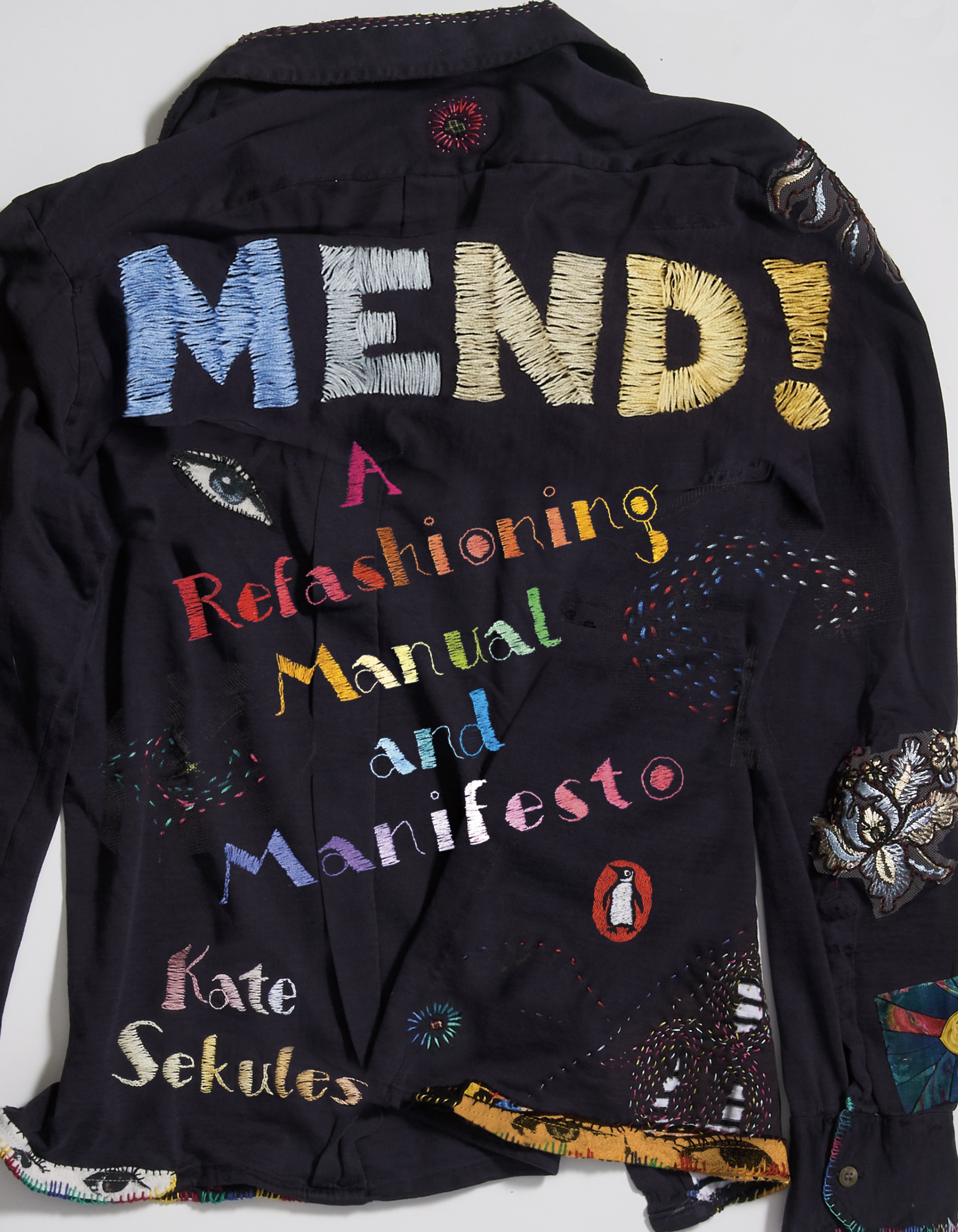

Cover of MEND! A Refashioning Manual and Manifesto by Kate Sekules (Penguin 2020). Cover design by Tal Goretsky. Stitching by Kate Sekules. Photo: Cathy Crawford. Courtesy of Kate Sekules.

MA: And it’s so relieving, I think, when you take that first action and you realize, it's going to be okay.

KS: Yeah, absolutely. And you know what's nice about mending visibly is, it doesn't matter if it's a mess at first, or if it's not okay. If you really messed up—and I very often do, and we all do—I like to double down. More is more. Just go over it again with another mend and it ends up possibly even better. So that's a method. It's an official method of mending. [laughs.]

MA: I want to talk about that a little bit more, cause I know that is one area where you really focused in with visible mending as opposed to invisible mending and more is more is more. You've really made that part of your manifesto. So I'd love to—oh, sorry?

KS: I said, "Oh yeah."

MA: I'd love to understand why and how you kind of centered in on visible mending as opposed to invisible or even other ways to act on garments.

KS: Good question again. It's fundamental that difference because invisible mending to me is labor. And throughout history, the mends that people have had to do to stay dressed have been as invisible as possible. And if they're not invisible, they cause shame. We all know that history of mending. Even if we haven't thought of it as history, it's obvious once you think about it. But also now in the current era, when clothes are so cheap, you're more likely to discard them and rebuy. Then invisible mending, it's much harder. It's just an altogether different skill. But the reason it's visible is because you're making a statement. It's very much of a deliberate act and a badge of honor and a display of your choices. And it's opting out of the fashion industrial complex, and it's an announcement that you're doing that and it does it all without words. And it does it as beautifully as you can make it, but it has to be visible. So I've sort of forgotten your—the question is about—[pause.]

MA: Why you felt—why you made visible mending part of your practice relative to other—

KS: Got it. So in fact, as it turns out, visible mending is a thing. I thought I'd made it up and then I was going to do a website, so I bought visiblemending.com. This is about five, six years ago. And, at that point, I looked it up and I found Tom of Holland. Very important in the visible mending movement, because not least he did the hashtag first, but he’s really interesting. Look him up if you—you've seen him in my book and you probably have become familiar if you weren't before, because he's fantastic. So I actually contacted him and said, "look, I've got this URL. I'll give it back, if it's yours." And he said, "no, no, do it with my blessing." So he was a big—I feel about him, that he was the founder, even though he doesn't think that. But in the current era of visible mending, as a thing, it dates back to about 2012 and him and a few others in England who were visible mending. But I didn't know that at the time. Meanwhile, back when I was like eighteen, twenty, I was doing it. I've got one thing left, which is from that ancient era. And it's terrible. It's so bad, but it is genuinely visible mending. And I remember my thought process at the time. I remember everything about it. It’s like when you haven't seen a good friend for years and years, and then you re-meet, and it's like no time passed. It was like that. That blue shirt that I did in lots of colors, that is the same, now all these years later, connecting it up. And I feel it's a fundamental human—like I keep saying about mending itself, visible mending feels very organic and it seems like what we need now in fashion. And I think of it as co-designing. So when you're doing visible mending, you're appending an additional weave structure, and you're co-designing with the original designer, you're doing something that adds to it. You're not just repairing it. So that's a very big distinction to me between invisible mending repair and visible mending modern. It's active.

MA: Hmm. [nods.] In terms of the skills, materials and techniques, what was your process of learning?

KS: Although I wrote a book about this, I'm not sure that I wrote that because it's been a lifetime of little bits and bobs, but certainly started with growing up sewing. You grew up sewing, didn't you? With your, I mean, I'd love to talk more about that, but I know that—

MA: It’s not my interview, Kate! [laughs.]

KS:—we will go there, anyway, back to that later. Yeah, so I grew up sewing, my mother mended. They were wartime generation, my parents, and immigrants—a German and an Austrian in London. And that was a big stigma. You did not want to be sounding German in England, post World War II. And so that's why I'm not bilingual and I should be, but anyway, it came along with a whole set of behaviors, including mending, making clothes, making do and mending, because that famous phrase “Make do and mend” was the World War II British—it's what it sounds like, it was coined to help people preserve for the war effort, and there was clothing rationing. So that was all around in my family. That was kind of the stuff I grew up with and from there, I could sew on buttons and do patches and it just wasn't something to think about. It was just a natural ability. It just came along with growing up. Anyway, later, much later now, I took it up again, properly and fulsomely and extremely. I don't know that I'd ever darned in my life, so I just taught myself. Now there are all these—including mine—there are all these new books on mending, modern mending. But there weren't really any books on mending. That’s sort of where I started to research it as part of the academic work, and got interested in mending as a subject and noticed that nobody had done it, has done the history of mending. But my early teachers were historic, late nineteenth-century manuals of mending. That's sort of where I learnt to darn. And darning was a great big issue and something that all, especially women, had to do. I mean, it's a bit more complicated than that I know now, but it really was a universal skill.

Left: Mouse-eaten sweater, February 2020. Right: Kate Sekules, Mouse-eaten sweater mended with endoskeleton technique, March 2020. Photos: Kate Sekules.

KS: Okay. Well, I mean I didn't only learn from books cause I knew the basics. So if you don't know how to darn, but you know how to sew, that's not a great stretch. It’s sort of obvious. Actually it’s a very good point because learning from books has enabled me to make all the mistakes that anyone would make if they didn't know how to sew in the first place. So I can help people better this way, because I had to do all the mistakes first. And in fact, sometimes I've incorporated and kept in—no very often I keep those mistakes because I prefer the look of something that is uneven. Partly because it can't be from a factory, but also because it's just my aesthetic. I find it more avant-garde and I'm an old punk. I like the non, the unevenness. So yeah, learning as a mixture of—I think everybody now seems to learn that way because we didn't all grow up—your generation, I mean, you didn't all grow up, well, millennials and gen Z, didn't all grow up learning from their mothers and grandmothers. [pause.] Or fathers. I know some fathers who do mend actually. But anyway, I know there's an elegant word for it, that passing on of skills down the generations. Since we've lost that, or we've got a hiatus in that, the way everyone learns is now from a mixture of online, and obviously now YouTube is huge and—sort of lost my thread a bit. [pause.] Yeah, I've lost my thread. Learning, not from a person. It's what you were just saying actually, about when you've seen the objects that we've been studying in real life and it's a revelation. So, with sewing, I think it's going to be incredible when we're back in person and can have in-person sewing workshops and mending workshops because in this intervening year of no connection, but all virtual learning, I think we've missed out on the haptic and human connective tissue of learning to mend. I'm teaching IRL for the first time in over a year in May. It’s so soon now, at Winterthur [Museum].

MA: Oh that’s so exciting, in Delaware.

KS: Yeah.

MA: Nice.

KS: Yeah. That'll be exciting, cause that is gonna be people in a room.

MA: In terms of your periodic table of mending elements—

KS: [laughs.] I’m glad that you mentioned that.

MA: Could you tell us some of your favorite techniques.

KS: Yes. Thank you for mentioning that. Where is it? I'm going to have to look, because I don't have it by heart. All right. So this is where I discover I don't have my book. [laughs]. Oh, there it is. I knew I had one somewhere. Yeah, I mean, I did that because, well, A, I think it's hilarious. And B, I wanted some structure because there's no structure to this, and there needs to be for people to be able to get on board with it. People are kind of alarmed by zero structure, so just do something to help it be understandable, and envisionable—is that a word? The one I've sort of invented accidentally, one that I slightly regret, which is patchiko, a patch-sashiko hybrid. Patching. And sashiko stitching, it's very abused. The cultural appropriation in visible mending is appalling. And I'm always lecturing about that, especially with Sashiko and Boro, which we can go back to in a minute if you want. But you know, I say that, but then I did it. So this patchiko thing is such a great technique. It's sort of my favorite because that's the one I teach first and most often because anyone can do it and it's really easy and it only exists in visible mending and It's almost universally applicable. It's not much good for knitwear, but it is for just about anything else. And you just put a patch over a thing and stitch back and forth on it, or you can do all sorts of variations and make it very complicated and ornate if you want. But it's as simple as some running stitch on top of a patch without any hems, if you want it to be. So I love that technique cause it's so egalitarian. The structure that I did in the periodic table is playful and let’s just leave it at that. Some of them really don't need their own categories, but on the other hand, as I did this, I realized, yeah they do belong actually in elements. There’s the gases and the heavy metals and just like the elements, they do belong in groups. The group of darns—I can't pretend otherwise, darning is my favorite. It’s just the most satisfying, versatile, infinitely variable. And menditational. It's very soothing. You can do all sorts of incredible patterns with it, you can do it just straight, plain weave type darn in one color. It still looks incredible. Darning is magic to me. I just think it's an extraordinary technology, as you are actually weaving a fabric in a fabric. It's an appended piece of fabric that you're making live onto another piece of fabric. I just think it's—I don't know another word—magic is the best word for it. Have you done it?

MA: I haven't. I haven't darned. I've mended, I haven't darned anything. But honestly, I'm, I'm very excited to try. [chuckles.]

KS: Yeah, we'll do a darning session.

MA: I know!

Left: Moth-eaten knit sweater, 2017. Right: Moth-eaten knit sweater mended by Kate Sekules with multicolor darn technique, 2021. Photos: Kate Sekules.

KS: Oh, darning circles, by the way, darning together is just—mending together, in fact, just mending circles, it's so old fashioned. And yet I think when we do it now—you didn't ask this, but I'm saying it anyway—when we do that now, it is a—I keep using the word modern, but it is forward thinking. It's funny that something that's so archaic has really flipped into being almost avant-garde—no, what's the word—almost subversive. Yeah, but okay. [pauses, and waves hand.]

MA: [laughs.] No, give us all of it, Kate.

KS: No, I’ll come back, it’ll come back. But let’s go to another moment, something that you wanted to ask.

MA: I wanted to ask about some of your vintage pieces, because you mentioned earlier that clothes carry stories. They carry narratives. Is there a piece that you can tell us a story about?

KS: Just about every piece I own. I know you've seen the vestiges of Refashioner, but this sort of started when I was a magazine editor and writer for years and years and years. And then those magazines all died and I thought, what should I do? I will go to my love, which is old clothes and make this thing that now is everywhere like Poshmark and the Real Real. And I did the first one of those and it's called Refashioner, barely sort of sitting there as a kind of vestige now, just as a show thing. But it was to pass on your old clothes, and I'm mentioning it now because it was about the story—you were not allowed to upload anything to your closet—you had your personal closet, if you remember—without the story. So everything in it had its story attached. And to me, that’s clothes. Every garment that I own has a story attached. And sometimes the story’s really boring. Like I got it on sale or I saw it and I wanted one just the same. Those are still stories, but then you wear this thing and it becomes part of the fabric of you and it incorporates itself into your history and you embody it. It embodies you. It’s a mixed bag. I don't know who's wearing whom really. It's part of your life and it's your second skin, but it's who you are and it's who you show you are to the world and all of these things that are—I mean, you understand? I just know you do, you're a fashion person and a costume history person. People don't necessarily think about it, but I'm very happy to see it more and more and more spread out into general understanding that our clothes are more than just the thing that you're throwing on in the morning. It's something to care for. So I collect them. I always did. You could think of it as overshopping, but it was always old clothes from the start. I began by going to Portobello Market when I was twelve on my own. You could find incredible, historic pieces then for nothing. It just wasn't valued at all. So it was an education in costume history, but it was also a feeling that I got from these clothes that there is a history there. Each of these things had a life before they came to me. And now I look back and I realized that right back then was learning how to kind of feel something from a thing, not just have it be inert. That clothes, in particular, because they embody so much, they are part of you so much, and they literally have bits of—I mean, it's gross, but you know, they have dust and skin and stains and you wash them when you get them, but they still have traces from the previous lives. And to me, that is moving and fascinating. So ones that I own—well, this I'm wearing—look, actually, this [stands up in front of camera and gestures towards buttons on front placket of dress] see these, I replaced the buttons because they'd become crazed and they were splitting. It's a forties' crepe dress that my sister got me when I was about fifteen. And you could buy these things for twenty p, for nothing. They could just be easily found. And it's way too big, but it's really comfortable and it's got a pocket and I've always loved it. And then recently I did that button thing. So it's associated with me, with my sister. She's eleven years older than me. That's a lifetime of stories and relationship right there, but she taught me by accident and deliberately about clothes by being—she had a hippy Afghan coat, I’ve written about this in the book, some of those things, the Biba thing, Biba I worship [raises hands in gesture of praise]. And did then, still do now. So, every garment has a history, some more than others and some are really only good because of their story. And I feel that we've all been wearing those this year. Who hasn't been slobbing around in their favorite soft sweatshirt? Those are every bit, or I think actually more valuable than the fancy thing you got from some designer. Those are irreplaceable. And I feel very bad for anyone who Kondo’d their old clothes—Marie Kondo, who told us to chuck it all out. Well then, no, say goodbye to it nicely, but get rid of it. De-cluttering is an abomination and we need to now be re-cluttering—or no, we need to be tending. So I think of clothes as little—I think they have little souls. They're like pets and there’s an aliveness to clothes. So mending is all to do with that as well. Mending is to keep them alive and to honor them and to add to those stories with your labor and your attention and a visual that you find pleasing.

MA: That resonates with me so much. And that line where you were like “who's wearing who.” [laughs.] I feel that on every level. It's just amazing. I was sitting with my mom a couple of weeks ago and she could tell me every wedding she wore this specific embroidered lace to, because in Yoruba culture embroidered lace is part of the textile canon. And I was like, it's been thirty years! [laughs.] You know? And so when you say that clothes have stories and clothes are embodied, we associate them with specific memories, I feel that on every level. And just noticing that relationship that we have with our clothes is such a [pause.] uh, it's indescribable, but you just used the whole bunch of words to describe it. [laughs.]

KS: Well, I don't know how that came out, cause I wasn't really listening to myself. [laughs.]

MA: Don’t worry, when we transcribe it, you’ll know. [laughs.]

KS: Okay. Well, I hope it made sense. I do feel very strongly about it and just—I know you understand, that's completely just so delightful for those of us who get this to be joining up in various ways. And that's sort of being enabled partly by technology. There's some of it going on in Instagram, but it's not really, cause back to the thing of you saw the actual object in the Brooklyn Museum this weekend, and it's so different. There's nothing like the presence of you in clothes, and how you feel inside and what you then project to the outside from that. So mending—to get to mending again—it's just really an extension of that, all that universe that you love as well, that you and your mum—love that! All the weddings, to me, that's exactly the same. I can remember—certain things that are occasion wear, that I wouldn't wear any old day—I can remember every single time I wore them. And I’ve got a terrible memory.

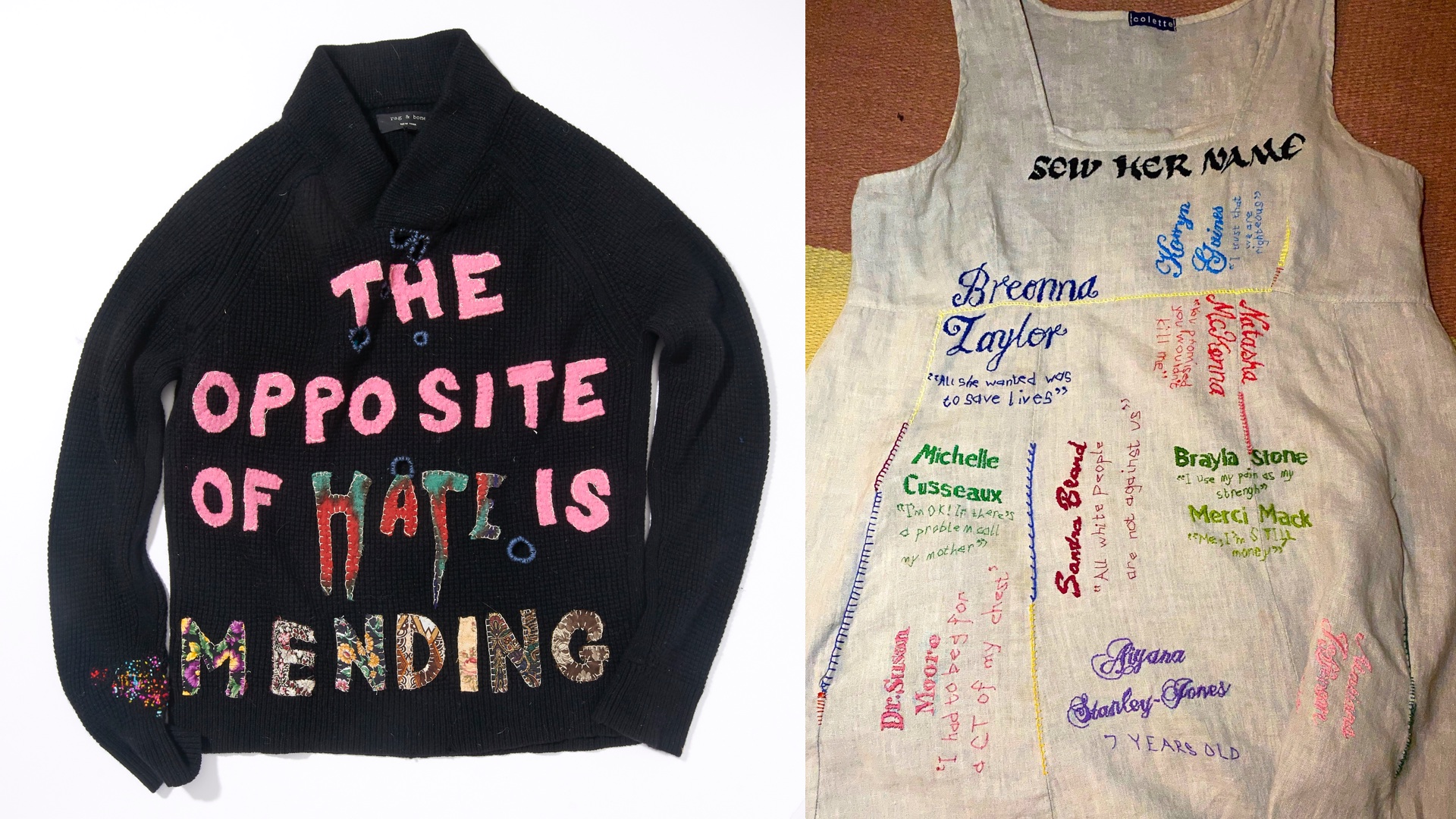

Left: Kate Sekules, “The Opposite of Hate is Mending,” embroidered and mended sweater, 2018. Right: Kate Sekules, embroidered and mended “Sew Her Name” dress, 2020–present, inspired by the #SayHerName campaign, led by Kimberlé Crenshaw and the African American Policy Forum. Photos: Kate Sekules.

MA: So since we brought up Refashioner, I do want to talk a little bit about the economic aspect of your craft and your practice. Could you tell me more about some of the business ventures that you've undertaken in this field?

KS: Okay. First, I have to say that business and me, we do not get along at all. I'm rather, I mean, talk about Marxist—I’m kind of that way, inclined very much, actually. So I don't believe in the fashion industrial complex, as I put it before, and I find what's going on now is absolutely abominable and appalling. It’s unsustainable in every possible sense. Refashioner was meant to be an antidote to the way that we consume. And then the back of book, the chapter “Whether” in MEND! is this vision, in a thousand words, of how we could consume better and much more fulfillingly. And that includes sharing. So my so-called business venture Refashioner was viable and it's in fact proof of concept, has been done by others. Actually I got to about 10,000 members, which now I look back, I think God, that's amazing. But in Silicon Valley terms, it’s pathetic. So that's how I thought of it at the time as pathetic, but I should have perhaps been more proud of the way people were embracing that, because the idea was to share. Refashioner started as a swap. So you uploaded, as I said, with the story, your good things from the back of your closet. It wasn't any old stuff. It was only the good stuff. And I wanted to get my hands on everyone's, to be honest. And I wanted everyone else to be able to. So the vision was of sharing and trading, and doing it personally with the meaning still attached. So that's how I would like business to be. And that's how I saw the possibility of clothing businesses in the future. And I'm pleased to see that is happening, but you know, it's still a lot of Silicon Valley trying to make the money off of the rest of our clothes—that creaming off the value, the profit. When as owned clothes—I call them owned clothes. They're not pre-owned because they're always owned and then they're owned by someone else. Clothes are owned. Selling owned clothes to someone else, when you do it through a platform like the Real Real, Silicon Valley is getting a profit and the clothes are getting exploited. And that's why I'm no good at business because I would rather not have anyone make any profit beyond what they need to stay alive. And that's not really what people want to invest in, but then, I didn't really want people to invest. I wanted it to be self-sustaining. And so these visions of business, I really hope that's where we're going in the future because we have to be. It's so obvious to me, I don't even need to say it out loud, but the inequitable business practice today is just—I don't even know a bad enough word. It's horrific. And fashion is one of the worst offenders, the way that's structured. I didn't really answer the question, did I? Cause I went on about business.

MS: Do you see business being any part of your future? Do you see yourself playing a role in changing the business of fashion?

KS: Yes I do. I do, but as a—I won’t say influencer, cause that means something completely different—but I want to have a say in it. I want to be on a platform talking about this and spread that further because it turns out—it sounds like a humble brag. It's not, I do have just this ridiculous crystal ball thing that I get onto something like seven years early. Like women's boxing, it was actually a bit more than seven years early. And neighborhoods. If I could only have bought a place in the neighborhoods I lived before other people wanted them, I would be rich. In this case, I think getting to something too early is an advantage because I feel that I am looking into a future that is going to happen and that I can help along. So that's what I want to do in terms of business. I would rather make a living as a writer slash academic kind of educator type person. And hopefully, I’d love to be a consultant in museums, helping mending be something worth looking at in its own right. That's what I'm doing at BGC. That's my dream. So that's my personal “how I want to make a living,” but I would like it to be possible for people to mend for a living. And it's beginning to. It's really happening. And that is a major—I think that could be so—they call it disruptive, but in a good way, disrupting the models we have now, which are incredibly disruptive to people's lives [chuckles.] and destructive. Interestingly, mending can be mending in a bigger way. Mending can help mend the structures that are abusive to human rights in clothing.

MA: That reminds me of something that was in the essay Sew Her Name [referencing Kimberlé Crenshaw and the Say Her Name project] that you wrote as a companion piece to the Sew Her Name dress where you kind of closed it with “this is not a master's tool” [referencing Audre Lorde.] Can you talk more about that? About hand sewing, about mending, and visible mending and what it means to be not a master's tool?

KS: [chuckles.] Well, I think that the needle is not the master's tool because it is sort of the opposite. A needle has been the instrument of women's oppression for forever. And yet, also the instrument of women’s, mas—mistressy. See you can't say mastery, and so there's not a good word, but anyway. It's hard to not be really clunky and obvious when you use mending as a metaphor, because it is so obvious. We need to mend the world. We need to mend—repair and reparations, especially with race in this country, are just fused. And yet, it's not making an analogy between—the scale is very opposite. I said it in the essay already, but it was really hard for me to go to that territory at all not so much because of being white, but because of being English and not from this culture at all. I don't—did not understand race in America. I've lived here for a long time and I still didn't think I was allowed to talk about it or go anywhere near it. And then suddenly last summer because of obvious reasons I was just flipped completely on the other side and it—honestly, I don't know if I should say it, but I will say anyway, it was a relief because I thought “of course it's mine as well.” It's humans. It's all of ours. And now I can join. I was so grateful, in a way, to join in. And it turns out that the way in was just sewing, because I didn't know how else to start to try and make some kind of difference and to communicate.

[End of interview].

visiblemending.com

refashioner.com