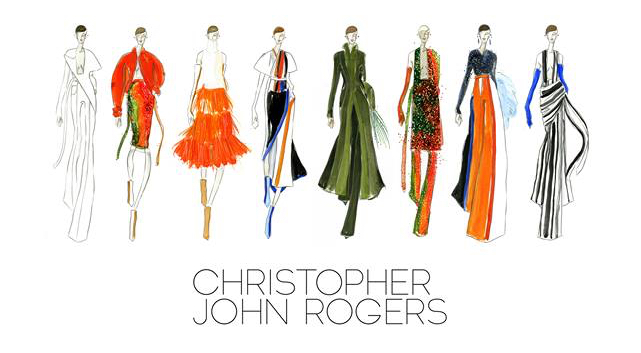

Christopher John Rogers

Fashion Designer

Conducted by Jaime Ding on April 8, 2018 at Brooklyn, New York

Christopher John Rogers in his bedroom studio, Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brooklyn, New York, 2018. Photo by Jaime Ding.

The interview was conducted in Roger’s bedroom-studio in Bedford-Stuyvesant, in Brooklyn, New York. He unpacks his education, his influences, his drive, and his work, looking to the future of Christopher John Rogers. In his deep dive on his recent past, he reflects about topics such as blackness, queerness, representation, and the people around him.

Transcript length: 1 hour 9 minutes

Jaime Ding (JD): All right, this is Jaime Ding, and I’m with Christopher John Rogers for the Bard Graduate Center Craft, Art, and Design Oral History Project on April 8, and we’re in his apartment in Bed-Stuy. Thank you for doing this with me!

Christopher John Rogers (CJR): Of course.

JD: I’d like to start at the beginning, and I feel like, this means Buchanan Elementary in Baton Rouge, Louisiana.

CJR: Yeah.

JD: Yeah? Would you agree?

CJR: Yeah, for sure.

JD: So can you speak a little bit about how this path got started, what about Buchanan Elementary spurred this, or if anything in school actually did, or if it was more, like, outside?

CJR: I think like—it’s interesting because obviously in the moment I wasn’t thinking about my future, but I’m really thankful to my parents for putting me in an environment that was, literally, so diverse, from kindergarten.

JD: You mean Buchanan?

CJR: Yeah, school. And that impacts the way I view references. The way that I, like, interact with people, who I feel comfortable around. Like if a space is too white or too one thing, I can’t, don’t feel comfortable. I have to have a bunch of different types of people around me. And like, cultural influences—I have a bunch of different kinds of—I really draw from mid-century art, Dadaism. I feel like that range of references was sparked by going to school with a bunch of different kinds of people. So obviously that was that, and then, I moved schools, to Brookstown.

JD: Oh, I didn’t realize. When?

CJR: I can’t even remember.

JD: [laughs.]

CJR: So I moved schools around first or second grade. I went to school there but, I don’t think they had like, a Talented [Arts] Program. So I went there it was really cool, met a bunch of cool kids and then I moved school. I was so upset, because I like enjoyed myself so much. And so they dragged me out of this school kicking and screaming and I was like oh my god I don't wanna leave and we basically toured this other school that was similar. I was in enrolled in actual art classes, I like, took painting, drawing. It was like two or three days in class they would take me out of class. And I would learn how to sketch and all that stuff. That was like second grade up until fifth grade, elementary school. And, around fifth grade when Project Runway came out. And I was like, what is—I was just like, on TV watching a bunch of shit I wasn’t supposed to watch, a bunch of adult shows, and there was this dark room, and I was like what is happening. I just saw amazing things coming from behind a scrim. And I didn’t even know what that was. In fourth grade, I was always into like anime, manga, cartoons, comic books. I would always draw comics. My friend Katherine was like, why are they always wearing the same thing, you should switch it up. But like, Ash Ketchum and all these people wore the same outfit, why would I change the outfit? But I like, explored it and it was fun, making these characters—how little details could automatically change how you perceived the characters. The more I sketched the clothes the more interesting I thought that was, and my experiences being execute what I had in my head, from like second grade on, influenced how seriously my peers and my teachers took what I was drawing. They were like, oh okay you’re doing this and you’re doing this a lot. So I was like, okay this is what I’m doing. I was looking up different schools in elementary schools like Parsons [School of Design], FIT [Fashion Institute of Technology], SCAD [Savannah College of Arts and Design], CSM [Central Saint Martins College of Art and Design].

JD: Wow, already?

CJR: Yeah just because I was like, "how are people doing this?" So that was kind of like, how it started, went to middle school, just kept drawing different things, and making mini-collections and everyone was like, you're still drawing this. And I don't know, it just became a thing.

JD: The anime—you mentioned Ash Ketchum, which is Pokemon. So I remember the three big ones, Pokemon—

CJR: Digimon.

JD: And Sailor Moon, I guess?

CJR: Oh my god, Sailor Moon was my everything. Tokyo Mew Mew—any sort of like, ultra-feminine but still badass. Misty was great. Anyone playing tech-in, or video games, I was always the girl. I think a lot of gay men, or queer people can identify with that—like, being able to identify as someone else. Being able to be someone that doesn't have to be a stereotypical version of what a girl would be, or what someone else would be. And so, I mean, at that point I was playing games. But looking back, I'm like maybe that was a reason.

JD: Yeah.

CJR: And even in my work now, I think a lot of young, emerging designers—designers of my age—are kind of doing a lot of very—I hate the word unisex, but unisex clothes or clothes that can be worn by either gender that can seem a bit more, like distressed or purposefully ambiguous and in my work I think I try—it just happens to be very very feminine. But it doesn't mean that it's exclusively like, okay for women to wear it, or branded as women's wear. I try not to brand it like that—I just make clothes. And they're feminine, and if you're a guy, or a girl, or somewhere in between, or whoever, you can wear the clothes.

JD: I think we'll unpack that a little bit more in a bit, but let's continue with these formative years for a bit. But before you got out of Baton Rouge, was there anything else that really—teachers that you remember—like, in Glasgow [Middle School], I specifically remember that Ms. Geeta Dave said you were going to be a fashion designer after she saw your drawings. And so I guess, did anyone or anything particularly influence you?

CJR: I mean yeah, Ms. Dave, she was amazing. She was a really—it was weird, because honestly, like during school, I kind of didn't know if I liked her or not. There were days when I loved her, but there were days when I was like, I don't like you. But I think she also was like, really really hard on the students that she liked or people that she thought were talented. Like, she would be like this is a shitty project, why are you turning this in. And at the time I was like, she's attacking me, but it wasn't her attacking me, it was her seeing something in me and trying to push me.

JD: Yeah.

CJR: So I think, that was something. And I also kind of was like, she thinks it's shitty, I need to make it better. And I was actually getting better at the projects she was assigning me. And honestly, I was just really lucky to go to really good schools where I could be myself, like, dress kind of the way I wanted to dress, a little bit but with uniforms. We could always like, wear a jacket or do something weird.

JD: In [Baton Rouge Magnet] High School we didn't have any uniforms.

CJR: Exactly, and that was also interesting, like—Mr. Hotard was the art teacher. Like, all of my art teachers were so different. I can't remember her name in elementary school—

JD: Ms.Trish?

CJR: Yes. Oh my god, you're so good. Okay, yes, Ms. Trish was sensitive, she was really supportive, she kind of saw where each student was going and allowed and pushed them to do that while also exploring the basics of art. I always thought all of my art teachers were really good. Like, they paid attention to the students and the classes weren't huge so they could give us individual attention.

JD: Anyone who wasn't an art teacher?

CJR: Honestly, I think that, who taught calculus—

JD: I know who you're talking about.

CJR: Anyway, the calculus teacher, she was always really supportive. She would see me sketching the margins of like, equations or like whatever and she would come over and be like "this is really good, I want you to design me something." Like, every teacher that knew that I liked fashion and I was serious about it was like, oh you're going to design my wedding dress one day, you're going to do this. It was never like, stop doing that. It was never like—it always really supportive words. I think every teacher was like—I was kind of knew I was gonna do it and they're like, okay you're gonna do it. And that was it. I will say, also a lot of my really close friends in middle and high school, like my best friend Julie Liu. In elementary school we were really good friends and we would sketch together and figure out what we liked. In high school we did our first fashion show together, where we went vintage shopping. We didn't know how to sew at that point, but I was like, I have to do this fashion show because it was the first time I could put something out. That my voice—our voice. So we just went vintage shopping, took things apart and resewed them back together which is kind of like, the classic story of how people start making things.

JD: When was that?

CJR: My sophomore year.

JD: And you just put on a fashion show?

CJR: Well Brianna Harris actually organized it. And she knew how to sew, her mom was a seamstress I think. She made patterns, she fit everything to models, like, it was very professional. Her show was the last one, and it was like, it was beautiful, actually. I think our energy—this feels so bad to say—the frantic "we need to do this" that kind of body of work was received really well. It was so funny because after showed, like, everyone kind of left the auditorium. But we were like, wait, it's not done, the show's not done.

JD: Oh no!

CJR: So I felt really bad but it was interesting how people saw that as kind of like, a moment. But also even the way that she, and our friends from McKinley [High School], they all dressed alike and I hadn't seen that before. We didn't have money to like, buy Abercrombie or whatever so they went thrifting and bought dresses and cut them really short, and wore heels to school. It wasn't sexualized that they were wearing these clothes. They were kind of like we like this proportion, this looks good, this is me at the moment. Our parents were always like, what are you doing, you're wearing things that are too short or too loud. It was never about getting anyone's attention, it was about being ourselves finally, exploring clothes as expression, color as expression. And maybe bending the rules because they didn't make sense. Like, why could guys get away with a shorter short than a girl could. Why was that a distraction? And if was a distraction, can we talk about why it's a distraction and get to the root of the problem? As opposed to changing the way that people are dressing. And so that—those are still things that I try to unpack. Like, why should this person wear this, why can't they wear this. You know, and it's like, is the fact that when they do wear it, why is a shock? Should it continue to be a shock? Just all these things, that kind of influenced, and still influences the way that I make clothes.

JD: So these are all thoughts that you had in high school.

CJR: Yeah, this, and also trying to get through the math test. But also in the morning, there are so many things that I could wear. And also looking back, it's a very Southern thing to want to look nice.

JD: What do you mean by that?

CJR: I guess I'm jumping ahead, because I like to make connections with random things but, thinking about people that make clothes now [inaudible]. They make things that are a bit more distressed and maybe not so perfect. It doesn't seem that the point of the clothes is to be perfect. But when I work, I always try to think of like, both of those things. So being Black and being from the South, at least in my family, in my experience—whenever you leave the house, make sure you look like you have an address. Look nice, present yourself, don't get in trouble, blah blah blah. So whenever I saw everyone wearing jeans with holes, I was like, oh maybe I should try that out for myself. My mom was like, you're not doing that. If something was a little bit off, she's like, it doesn't fit right or this color doesn't match. My grandma always wore head-to-toe, like a color head-to-toe green, head-to-toe red, matchy, church lady. And that's also something that I bring into my work. Whenever I shoot a look, I love the visual tonality of a monochromatic look, I think it's effective and it's about the color and the emotion of that color. I also like hems to be perfect, I like things like that, but also the franticness of me and Julie doing that first collection, where hems were ripped and things kind of didn't match, things kind of off—me analyzing why a hem has to be perfect, trying to get to this perfect moment allowing the imperfection to be part of the design, and like, the equilibrium and exploration of that process is interesting to me. So I like for things to reach, or like, grow towards perfection but the process is also part of the work in a way, and should be reflected in the final result.

JD: And you also made things for people.

CJR: I was making things for Julie—again, we didn't even know what the fuck we were doing. Like the day of prom, everyone was looking nice and Julie was like, I'm not about to buy a $300 dress. And I remember at one point she thrifted something and we kind of just wrapped a bunch of fabric around her, and like, that was a look. And as she was dancing, it was coming apart—we were just having fun! It was just so funny.

JD: Wait, what thrift shops?

CJR: It was like, America's Thrift. This was when we had cars at some point so, we were going to Goodwill, the first one we went to was like, Happy Tuesday. I remember we would go and stuff wasn't cheap. It wasn't expensive, but it wasn't cheap. A jacket was like, ten dollars, which is like not bad now, but back then we were like, oh my god, ten dollars stop! So we went to cheaper places and bought shit and safety pin things and sewed things. Again, it was like we were trying to make it look great, but we have to put a safety pin in it, because we don't know what we're doing. So it was part of the work as well.

JD: So then, you went onto further education. I remember you did get into Parsons—but you ended up going to Savannah College of Arts and Design. Why did you pick SCAD over, I'm sure you got into other schools as well?

CJR: So the schools I applied to, I got into Parsons Early Action, I got into FIT Early Action. But I didn't get my Parsons acceptance letter until May. I got accepted early but they didn't email my acceptance letter. And if I had accepted it, I probably could have gotten scholarships and might have probably had more of an opportunity to go to Parsons, but at that point, we hadn't heard back yet, so we were like maybe I didn't get in, maybe I didn't get a scholarship, so that was kind of out of the options pile. And then, again, my friend Brianna went to SCAD for her first two years, and then moved back to Baton Rouge. But they were like, oh she's going there, it's a good school, maybe she can look after you in a way. You know, my parents were very like—no one ever really leaves Louisiana, or Baton Rouge. So, it's like, you're leaving, we don't want you to go to New York, we can't monitor you. SCAD's closer, they gave me a good scholarship, they went and did the whole persuasion thing and took everyone around and showed the best buildings and they had like, a lunch for everyone that was really fancy for the prospective students. So my parents were like, "this is great, you'll love it." I always knew, like I'm going to go to New York. Like, where else would I go? Or I'm going to like, London. Where else would I go. And I ended up going to SCAD. Me and my friends were actually talking about this yesterday, and we were really happy that we went. Because I think that I was able to really find my voice in a place that was more adjacent to the art world than Baton Rouge, but also not so crazy and hectic like New York. I also wasn't influenced by New York expectations about what kind of design I should do. The work was still about kind of like, a Southern point of view. I never considered myself Southern, or Louisianan. It was kind of like, I am me I live here. Especially having the internet, LiveJournal, Tumblr, Facebook, MySpace. You could look at people—even this website called LookBook, which Julie and I tried to do for a little bit—you could see people's stuff from all over the world, you could like, talk to people in Denmark and Morocco, wherever. Like, looking back, it's so funny how—even like, the debutante moment—which, I mean I never went to any debutante cotillion balls or anything. It's about kind of like, looking at people who are doing those things—it's so weird to me that that was a thing but also like, being inspired by the looks. The Mardi Gras balls that I never got invited to, but you would see people looking fancy. So that was kind of like, oh maybe is that something that I desire, is that something I want to participate in? But then also looking at my friends who were playing soccer, or like, how Julie would wear like, a corset to school with like, flat shoes. Or like, a fancy satin skirt with a tank top. And that mix of like, I don't care but I also care. Um—what were we talking about?

JD: SCAD? [both laugh.]

JD: SCAD? [both laugh.]

CJR: So that, I was able to explore those things without having to think about like, Black and White New York, or like, practicality. I didn't really start thinking about pragmatism in my work until I moved here. Because then I was like, oh I have to walk everywhere. Or oh, you can't wear heels everywhere. Or you can't wear a boot everywhere because you're gonna die.

JD: [laughs.]

CJR: You know? So, I was really able to explore the aspirational part of my work in school.

JD: So what was it like? What was SCAD like?

CJR: SCAD was um, really, slow? It was a good experience in retrospect, but there I was like, this is so slow what am I doing?

JD: What do you mean by slow?

CJR: It didn't have what I expected from a college experience. It was different than what I expected. It was, it felt very like, hometown-y. I feel like it's New Orleans mixed with Baton Rouge, but like—I don't know. It was really weird. It was like, house parties were—it was really weird. You have to go. Savannah's like really weird. It's like—I don't know. I was actually really focused on work. I also was a goody-goody. Coming from school, with my parents, I was like don't do drugs, don't drink. I didn't have a fake ID so I was scared about getting caught, so freshman year, sophomore year—I didn't have a fake ID. I only started really going out when I was twenty-one, in junior year, so everyone had already, like, fizzled out. They were like normal, and I was like whoo! Going crazy. So the first few years were like me working, taking it slow, going to the park. There wasn't a lot of things to do besides work and hanging out with friends, so it was kind of chill, kind of slow. Maybe if I had gone to New York, I would have tried to sneak into clubs, and do all that stuff. Because like, there weren't that many clubs to sneak into in Savannah, you just kind of like, walked around.

JD: Well, why don't you talk about the work for a little, the work that you were doing? What was your major? What was the education process like?

CJR: So my major was fashion design.

JD: Oh okay. [laughs.]

CJR: Yeah, and we took like foundation courses basically the first year. Drawing, blah blah blah. I was like, really bored, because I had already taken those classes from like, second grade. Like, basic drawing classes to color theory, which I love, I love that class. But having to mix colors, and like, a lot of tedious work and it wasn't fashion. I really wanted to learn how to sew properly. I wanted to learn how to make the ideas in my head come to life in a way that was real and tangible for people. So it was kind of frustrating to have to like, take all these basic classes. Well also not being able to do anything else, you know what I mean? So it was a lot of time just like, making friends and doing things outside of class. I would also do stuff last minute, and do it really well, and like, present it and be like, this is it, and everyone was like oh my god this is so good! But like yeah, because I've already done it before. But like, yeah that was that. Around the end of my freshman year, I finally took my first sewing class, which was just the basics, which I already kind of new a lot about, but I learned a few things, which was cool. Then, sophomore year, I was always kind of jumping ahead of the curve because I was so impatient. So I was always like, what classes do I actually need to take to be able to take my first real fashion class. And then, one was like, an apparel one, which is when you make, you drape a bunch of things and then you make one dress. So everyone was making like a basic, you know, little shift dress because this was our first time exploring the form. Then I was like, how complex can I make this. I wanted to make a jacket, I wanted to make pants, I wanted to do all this stuff, and then my professor, who is one of my favorite professors at SCAD now—then, I hated—I really did not like her while I was taking the class. I was like, oh, I've shown collections in New Orleans, I've done all this stuff, and she was like, I don't care. Looking back it was like, who cares, you know. But me, being like eighteen, nineteen, I was like, look, I'm doing cool stuff, and she was not impressed. She didn't care. I was really mad because I was like, why am I not impressing you because I'm trying to do everything that I can, but it wasn't about what you had done before. It was what are you trying to do now, in a way. She would really push me to not do what I thought that I could do to do more. She was like, if you're so good, then show me. At that point, I was turning in things that I thought were good, but then she gave me like a D and an F and I was like oh my god, I cannot fail this class. So, I would go every day and every night, even when I wasn't supposed to, and like, perfecting everything that I was doing and like, it was senior time. So, professors work with freshmen, all the way through senior, it's the same professor. So she was teaching her senior class, which is like senior thesis: huge body of work, crazy forms, all these things. So then I was looking at seniors but I was also doing my own crazy thing and they were kind of annoyed at me because they were like, why is this sophomore here when I have professor time because they don't get a lot of time with the professor. And [Professor] Satchi was like you're annoying me, you're annoying me, and I was like, I don't care, I need you to teach me this. And she kind of liked that because it was like okay—like the Ms. Dave thing. And so then I learned if you want something you really have to like, you can't think that you're special. It really humbled me a lot and I was like, thank you for that because there are so many people who want it, so you have to show that you want it. So I learned that from her.

JD: Who is she?

CJR: Professor Sachi [Sachiko Honda]. And there was also another professor named Dean Sidaway, we're still close now. He works at Pratt now. He taught Intro to Fashion Design, which was like flats and sketching and coming up with a collection, coming up with a concept. He went to school at CSM, I think, or London College of Fashion. He's British. But everyone was kind of doing the same concept. At that point, I had already experienced Satchi a little bit, so I was like, okay, just do the work, keep quiet, be nice. My first concept was like, this dinner party in the fifties and like, she invites someone over who's a murderer and they killed the family. This eye-roll concept, but it was really cool, the images that I picked were really great. And they weren't like, current runway images. Basically this [points to wall of samples] kind of abstract things, and things that were a bit more moody. And he really liked it, and I would always try to overcompensate by doing more sketches and come into extra-curricular sessions, and then at one point he was like, Christopher, what are you doing? And I'm like, what do you mean? He's like, you already know what you're doing. He's like, why are you even in school? He kind of told me that. It made me feel good, because I was like, okay, maybe I am doing something right? It really made me believe in my point of view and what I was doing, even though it was so different from what everyone else was doing. And that also kind of, formed the way that I experienced other classes. He was the only professor to ever really tell me that. Well also critiquing things and saying, you can fix this. While he was also like, you know what you're doing, something right, so much. So when I went to other classes that were about creating collection, I went with the same process and it was very different from what everyone else was doing. And the professor was sort of like, okay, make the shapes more amorphous, make them a bit more conceptual, and at that point I had already done that in middle school and high school—and like, elementary school I was drawing weird things, making weird conceptual things. I had already gone through that process and I wanted to make things that were a bit more concrete and real. So I would sketch those things, I would sketch things that were feminine, and I would sketch things that were maybe not such a stretch, that were glamorous, and were things that you could actually see on a runway. And they were like, what are you doing, like, stop doing that. And I did it anyway. And like, I got Bs, and As, at times, because like, it was good work, you know. And I remember there was this competition called Joe's Blackbook. The only premise of it was to design a collection that's you. And it has to be, like ten looks or something. It was just like, a visual thing, you didn't have to make anything. So basically I did the project, the first part, and then the Dean of Fashion at the time wanted everyone in. And everyone was like, oh yeah, and my critique went really well, blah blah blah. I think my theme was like, these weird jelly animals under the sea mixed with 1930s—like, the Met [Metropolitan Museum of Art] has a website and they show the fronts and backs of a bunch of different dresses. So I was looking at dresses from the thirties, but only the backs and if the backs were the fronts, and just thinking about the body in a different way, and like, a bunch of different things. But the effect was quite glamorous, a bit weird, a bit off, but it was beautiful. It wasn't like, what they wanted it to be. It wasn't student-y. And so I showed it to him, really proudly, really excited to see what critiques he had to improve it. But basically he was kind of like, this is dated, this is tacky. Like, I was doing puffed sleeves, I was doing ruffles, I was doing hot pink. And he was like, this is tacky, no one's wearing this, this isn't modern, this isn't a very New York, you know, submission. And so then I was like, yeah, but like, the project—even though the company Joe's Blackbook, is based in New York, and a lot of the previous winners, people that placed, did things that were black and white, grey, graphic, work-y, maybe a bit weird, like Comme-de-Garcon-y, but wasn't where I was going. And then, he was like, yeah, it wouldn't place. And I was like, yeah, I know, but the premise is to use something that's you, and no one else is doing this, so maybe it's a good thing? Even if I don't win, for them to be like, oh he has a different point of view. And I always saw every submission of a project or a competition to be an opportunity for me to show my point of difference. In a community full of artists kind of, maybe, touching the Zeitgeist of what was happening, which was minimalism at the time, amorphous shapes, blah blah blah. So he didn't move me forward. I was really upset about that. But I kind of got over it. Moving on, later that year, there was an assignment to design a collection for another house that already exists. So I chose Lanvin, and it was very feminine. I did the same thing, I did like, puffed sleeves, I did sort of, portrait necklines, square, really eighteenth-century shapes mixed with trousers and turbans and jewelry. Crazy. But really feminine, really beautiful, blah blah blah. Again, she was like, this is dated, no one's wearing this, this is weird, blah blah blah. Like right after that, JW Anderson showed his collection and it was puffed sleeves, and that's what started the whole puffed sleeves thing, which is kind of still happening now. So, it was so weird how I was kind of approaching something that someone had also—who they liked was thinking of, but because that person did it, then it became okay to do. But because I was doing it, it was weird and so I was a bit angsty towards school, I was like fuck this, like, you don't get me. And then, of course, I was thinking about jewelry, I was thinking about turbans, I was thinking about all of these—I was thinking about Africans in Europe during eighteenth century, and so I did a lot of like, French portraiture and like, the woman on the swing. Portraits of Black people at that time as well, and like, melding a bunch of different cultural archaic things. And so, then, all of the sudden Gucci started doing lots of bling, glamour, mixing different things together. So it was just interesting how I was trying to do the same thing and they weren't into it. So again, I became angsty, blah blah blah. So my final senior thesis was kind of like, a big fuck you to the program a bit, because I just did whatever I wanted. And the Dean wasn't having it—he didn't like it. We got into this little tiff, this altercation. But I ended up being sponsored by Saga Furs, Swarovski, like, really big companies. I stayed day and night which Satchi had kind of taught me about. Like people were going up the bars and I was out cutting patterns. And I was like, this has to be like, good, because I couldn't like, with everyone back home being like, oh you're going to be a superstar, you're going to be a designer. It was kind of like, I didn't have any other choice in my head, then to like, make my friends and family proud or whatever. So okay, I was like I have to do this and I can like, rest later. So, I did the collection, and then, before the fashion show, there's this jury show where people from the industry and New York and LA and some from Europe come to SCAD, and they sit in the auditorium with all of the seniors, all of the professors, and like, each collection comes out and all the models stand, they judge, and people all go like, oh, clap or whatever, and then go away. So I was like waiting, and I was like, when's my collection coming out blah blah blah, I was like front row, so excited. I didn't see it, I was like, "oh my god." And then it came out last. It actually came out last. And then, everyone was like, silent.

JD: How many people were in the class?

CJR: It was two campuses, so I want to say maybe, eighty.

JD: So after eighty, yours came out last. And it was dead silent.

CJR: Yeah. And everyone was like. Because I didn't notice, but I actually met with an old classmate who was a Masters student who also showed then. We got like lunch, a few weeks ago, and he was like, you don't know this because you were like, in the front, but like, I was in the back with the professors, and everyone was like, oh my god, what is this? And then he was like, this look so good. And they were all like, yeah. And they all started clapping, and that's when the clapping started. And it was just like—it was so good. And—

JD: Yeah!

CJR: And I just felt like, so, it was all worth it, like it looked expensive, it looked like a runway and wasn't a student project. It wasn't crafty. It was kind of, quite different from what I showed in high school, you know what I mean? You know, I was just really happy with it and it kind of showed me that it's like, working. Or that, like, what I'm doing is kind of, like, good.

JD: Yea. Even though everyone at school was kind of like, it's not, or—

CJR: Yeah. Or a couple of the—it was kind of like, the fuck you worked. Because he didn't like it, but because everyone else liked it, it was okay, oh okay great.

JD: The dean, particularly.

CJR: Yeah.

JD: So now we're here today. Well, how would you describe yourself—like, what terms would you use to describe yourself.

CJR: Like me?

JD: Yeah.

CJR: Um. Obsessive.

JD: Oh, I mean like, professionally, like are you a—

CJR: Oh, I see. Fashion designer.

JD: And have you considered any other kinds of terms? Or what do you not consider yourself?

CJR: It's funny because like, I've been doing a bunch of, like, visual research for this upcoming show that I'm doing in September, and I kind of feel like—I know that other mediums in which I could express myself, like, I want to explore painting more, 2D forms. I want to like, do more like, soft sculpture. I want to try ceramics. So, I guess I wouldn't say that I'm not anything. I don't know what I would say that I'm not. I don't know. I guess it's complex. But I guess for ease of understanding, I would just say I work through fashion. Like, I use the construction of garments as a medium. Yeah. Right now.

JD: And how did you record all of—you mentioned when you were talking about college, you mentioned all these ideas in your head. How did you keep all of those, or record them as you were going along?

CJR: I have this really big process book. And so I would take all these images and put them together. I would make little collages of three images on each page, and then sketch into them, mixing the references. Like, for example, I'd just take like, maybe three of these things [points to images on wall] and then like, somehow come up with something. And then I would explore that through scanning. I had this idea to do this graphic print, which has become a motif in my work, and I just got a banana leaf from the cafeteria and scanned it, moved it, and then like, made weird waves. It was just like a stream of consciousness throughout the whole process, and I just had to record it as part of my work. But a lot of it is just in my head. So it's hard for me to like, get it onto paper. But, yeah. A lot of it is just in my head.

JD: And then, right after graduation, you moved here to New York. You wanna talk about the past two years, and what that's been like?

CJR: Yeah. It's been fun. It was kind of hard at first. I moved here without a job, and I was actually staying in the room like, across the hall. I was just like, on a mattress in the apartment. And I moved here because I was like, oh that's what all fashion designers do, like, they struggle! So I kind of glorified that a little bit, and like, Beyonce had pulled the fur coat that Cardi B—Cardi B ended up wearing one of my senior thesis pieces. Beyonce pulled it, and she was supposed to wear it and I was like okay like, that's gonna be like, my big moment and then like, I'll be able to get a studio and I wasn't—I didn't know how everything worked. So I just moved here. She ended up not wearing it. I got a job at like, this Nigerian restaurant called Bukka not too far from here. And so I was just waiting tables and then like, doing whatever to make ends meet. And then I ended up seeing that Jonathan Saunders was the new Creative Director at Diane von Furstenberg. So then I was like, "okay, a job in New York that I could actually get excited about." Because like, I didn't really know what else to do except my own thing, but I had been applying anyway and no one was responding. So I ended up basically emailing them and then they were like yeah we'd like to have you come in. So, went in and had an interview, seemed to go well. Like my boss, Henry, my supervisor, ended up liking all of the work that I had done. He was like, oh this is really strong. So I didn't hear back from him and I kept on bugging him. I was like, answer me! Answer me! I had to do a project for them. Ended up being hired so basically for the past year and four months? I've been working there, kind of doing my own thing on the side and trying to solidify it as an actual business without even knowing how or what would be. Like, the steps to go about it. So I've just been making small lines of work and like, trying to get them in the public eye as much as I can to get some kind of collateral. You know, to have some sort of like, weight in saying this is why you should buy into the collection. This is why you should stock it in your store. Because as much as like sort of just making forms and like, using color as object and all these things, in order for me to keep doing that, I have to like, sell the clothes. You know what I mean? So it's been kind of like a process of figuring out how to turn all of these things into a viable business. And I've had some support from the CFDA [Council of Fashion Designers of America] and Jonathan Saunders. He left DVF recently this year, but he's been supportive in saying I should move forward with presenting a full collection in September like actually during Fashion Week so it won't just be like an Instagram release thing. So I'm trying to, or, I actually am going to be in that moment like with actual other designers, showing a collection.

JD: That's exciting!

CJR: Yeah! For sure! Making it in this tiny room! It's gonna be definitely a moment, for sure.

JD: Do you want to talk about your work right now a little bit? I noticed on your website you use the word “authentic” and can you explain what you mean by that?

CJR: I think it's just kind of about as generic as just being yourself and embracing all the nuances that make you you. Whether that's like, just everything. I think right now there's like—politically there's such a moment of people not liking authenticity and people loving it and feeling it's necessary to their existence like, be them completely. And I'm just trying to make work that encourages an exploration of maybe seeing things and liking them that aren't you or aren't popular, or aren't prolific at the moment. It's just kind of about saying oh, I like this. Try it on. Maybe buy it, let's repost it, let's talk about it. Um yeah.

JD: And do you have a specific person in mind when you are making all of these things?

CJR: I think it's really a lot about me saying I like this color. I want to make something in it. Color for me, I see that as a thing and an energy. Color for me is like, number one. So like I'll see this fabric and the color's great, and like, okay let's make this into a shirt, just because I want to see the color as an object. You know what I mean? It's not even so much always about the silhouette. It's really about this color feels great to me and it'd be even stronger with a matching pant because I think pants are great. You know? Like, it sometimes can be that easy. And like, all of this [motions around] can sometimes be boiled down, for me, about like, painting again. Okay this top with this, it's like you're a walking Rothko. And putting a corset on top of it not because it references necessarily the forties or fifties but because that can be another block in this painting. But maybe sometimes the fact that I made it into a corset is about that idea of femininity. So I'm not thinking about a person necessarily but maybe kind of about the way I want to see color, and then the people who gravitate towards that specific expression of mine tend to be people who are really confident in themselves who like to explore fashion as a way of expressing themselves. Because not everyone does that in such an explicit way, but I think the people who like my work or want to wear my work do that. They like to explicitly say I'm feeling this way today. Or I like to stand out in a different way.

JD: What does it mean for you to hand-make everything?

CJR: It's about a lot of attention to detail. It's just like me. I don't know. It's like, I don't know.

JD: Yeah I mean that's fine too. [both laugh.] I also notice that you've been talking a lot about historical references. How do you get at those sources?

CJR: We had a really big library. The New York Picture library is actually a really nice archive and there are things you can't find online there. So I'll go there and look through automotives from the forties or whatever. Sometimes the inside of that can inspire something. The inside of a car I'll be like, oh this looks like the inside of a vintage corset. So I'll make connections that way. The things that I make aren't necessarily about a theme but about making connections visually with things that I like and then making something that is adjacent to those things.

JD: Do you still think about graphic novels or manga?

CJR: I mean, all this stuff—I just come up with shit in my head. Now I'm unpacking it, but I'm really love graphic prints. Like not necessarily watercolor-ly florals, but things like that. [image of black and white print.] And I think that that comes from like, comic books and liking things that contrast. So I think about that. I think about people being very expressive, which I think comes from graphic novels. I think about people being superheroes, or superheroes within their own lives and taking a risk in whatever way that may be. Feeling young in a way, or youthful, or not feeling jaded. Being optimistic. I think all those things kind of come from that, in a way.

JD: That's a very positive outlook!

CJR: Trying right? [laughs.]

JD: I've also heard you use the term elevated to describe your style. So what does it mean for you to look expensive or to elevate the everyday?

CJR: I think aspiring to something that isn't—taking something that makes you feel comfortable enough and stepping outside of your comfort zone and maybe attracting a bit more attention. Saying I'm going to put the effort into not caring if someone else doesn't like it, or putting effort into like, refracting other people's expectations. Even for me, sometimes I make things and I'm like, this is a lot. How would I wear this? And if I were to wear it, I would have to not worry about what anyone else wanted to say. So it's kind of about elevating yourself to the point where you know that you are okay with your happiness and the way that you look regardless of other people.

JD: So the class is about craft and design, what do you connotate with the terms craft, design, versus art?

CJR: I think crafting for me is really considering the process of making something, more so than design. Design is like solving a problem for me, like this person needs something to wear to this, or I want to see this color as an object and in what way would someone want to invest their money and time into this object. And then art is all of this, the process also is art. Coming to the final design, product. And the way in which you make that a product is the craft. I think attention to longevity and sustainability and more purposefulness to the product or the object.

JD: Speaking of people who you've dressed, I mean you've dressed some pretty incredible people like SZA and Shea Coulee!

CJR: Yeah! [claps.]

JD: Can you talk a little bit about how you got to dress them and what that process was like?

CJR: A lot of it honestly is just—I'm always surprised because I just make stuff, and then people will react to it online. All the transactions and interactions have been online.

JD: Like through—

CJR: Through Instagram. Love Instagram. This stylist pulled a lot of our things and used them for this shoot which I thought was really beautiful and so I just started following him on Instagram and then I would like enough of his things at some point until he was like, oh who is this person. Then he followed me, he started styling Cardi B. And then I was like, okay who is Cardi B? Like, what is this? So then, her music was cool and I had heard about her, and I was like okay cool. Then he asked to borrow the coat for this big TV thing. So then I was like I don't know what it's gonna be, like maybe it's gonna be a bit too like, like the coat's already crazy so I wanted it to be a bit more sophisticated to contrast the expectations of what the coat would be. You know what I mean? Like you kind of expect to see a big fur coat on a hip-hop artist right. So then I was like, "oh like [higher voice] I don't know." But then I was like, "fuck it. I've had the coat for a year, I like her work, regardless of what other people would associate her with." So I was like, "wear it." She wore it and it was like a huge moment for us, and for her, and it gave us a little bit more legitimacy with like, dressing a big pop star, and then I guess with that, with people seeing the level of craft that we were able to achieve, then SZA's stylist reached out. Basically stylists reach out to me, and then we take these things and pack them up and drag them across the city. Or we ship them to LA or wherever they're going. And then, they like, have so many options. I was on SZA's stylist's Instagram for that video. I watched her story and it was literally like, a warehouse full of like, garments. And I was like, my stuff is there somewhere and she's not gonna wear it because it's like, there's Gucci, there's Prada, there's all this stuff. You know what I mean? And then so then, to my surprise, she actually wore something in like, a video and I was shocked and really happy and excited and all these things. Every time someone kind of famous or someone that people like, likes my work, I'm like, "that's weird."

JD: [laughs.] Who's the we that you keep talking about? You say we.

CJR: I work with my business partner David who like lives down the hall. Also designers say we a lot because there's like, a whole bunch of people that help make those things happen. Like, my coworker Morgan helps me with the prints a lot because she actually does print design. My friend Alex, who is the person who surprise visited me, helps me bond fabric sometimes or to sew something. I have friends who'll come over that will help me do a button. So it's like, a lot of people who will help me come up and execute all these things. And I like to give credit when credit's due.

JD: Can you also speak a little bit about that idea of challenging representation, like how you were talking about rappers and fur coats and how you go about doing that in your work?

CJR: I struggled a long time with the idea of like, being Black in fashion, in art. Me being myself and me not necessarily always aligning with people's expectations with being a designer who happens to be Black would produce. That's obviously a big part of everything. Like, for a long time, I was like I don't want to be someone who dresses just Black women. There's a lot of support within—like, Black artists and Black stylists like to help Black designers, and so a lot of Black artists or musicians or models in Black designers' work. And I kind of wanted to push beyond that and be more than just kind of one thing. [sighs.] But I was kind of like, people who want to support me I should let them support me regardless of people's expectations and my expectations of what I should—like, I'm just gonna let shit happen, you know what I mean? So there's that aspect of me trying to reconcile who I am with who I think I should be in order to be successful.

There's a lot of like, me thinking that guys should be able to wear dresses, because like, duh. Or like, girls should be able to show cleavage or not, in the same day, because why not? So I like to make things that people are able to like, explore expectations with while also still feeling comfortable. Like, I've done like tulle shirts before which are quite—it's just like a tulle button up shirt, it's not crazy. But it's also kind of like, you could wear it without a bra and still like, be completely covered up but also like, not at all. And so like, exploring expectation through clothes. You could put a jacket over it and still be covered up and still be sexy but also have it not be sexualized at all. You know what I mean? Even just the politics of putting someone in something means something. So there's a dress, in the look book it's shot twice. It's shot on my friend Christina, with like, pants and it's quite beautiful and a bit monastic. It's a long dress and it has a collar and she's wearing pants with it so you can't really see a lot of her skin.

And then I put it on a guy backwards, my friend Jake, and put it with a pencil skirt and unzipped it so you could see his butt cleavage and it was like, so sexy and also so feminine and like, I'm not sure which way he identifies, I think it's as male but the feeling was feminine. Also I like making things that are so simple but again, putting someone in it means something. So it's like, it's just a pencil skirt, it's a dress, quite simple. And then the politics of unzipping, of him being a guy, of him like, posing as feminine in the garment was like— And also to me, I feel like, I'm a very feminine person but I'm also not as stereotypically femme person in a way. Like, I'm femme in my expression I think quite often, and I wasn't comfortable expressing my masculine side, because people never attributed that to me in a way. Like, I always wore bright colors, I always like, did my thing, had a little sparkle on, had a white pant on. And like, I like to explore the nuances of how to express femme-ness or masculinity or all of these things subtlety, because that is a fact of life. I think queerness right now, a lot of it is in your fact. Which is great, because that's true. And I've done drag before and I do drag sometimes and you know, that's very in your face. And there's also times where like, you wanna like wear this [sweeps hands over self] like, a button up shirt, regular pants, Doc Martens, and then like, I might carry this, you know? [grabs a shiny beaded yellow clutch off a rack.] Like, just because I want to. I think the subtleties of extravagance and performance interest me a lot. I think that also ties back to authenticity and feeling like you can be a lot without saying a lot.

JD: Amazing. My last question to wrap up things—what's next? I know you have the show in the fall, but also what do you ideally want in the future? Not only for yourself, but maybe for the fashion industry?

JD: Amazing. My last question to wrap up things—what's next? I know you have the show in the fall, but also what do you ideally want in the future? Not only for yourself, but maybe for the fashion industry?

CJR: I think I'm trying to explore—obviously I'm doing the presentation in September, but exploring myself more, and trying to find articulate and powerful ways to say what I wanna say without having to yell or fight for attention. And also to make product that people can aspire to buy and have for a long time and feel themselves in it, and enough in it, without just like making more stuff.

JD: Like, not like extra.

CJR: Or, it can be extra because sometimes that is part of my product, the things that I make. It is extra, but I don't wanna just like, make two hundreds black shirts that don't add anything to any conversation. I don't want to just make product just to sell. I want everything that I make to have intention and like, be soulful. And I want, like, more designers to be able to express their points of view that are maybe are different than what's happening now. Or what has happened before.

JD: Do you think you'll continue using Instagram?

CJR: For sure. Instagram's a really great tool. I've met so many influential people through it and like, talked to so many people through it, and people are able to connect with and my work on it. So I'll definitely be using it again.

JD: What's your process of thinking about how to craft your Instagram brand?

CJR: At some point I was like, "Oh my god I have to post more because I want more attention." Like, I want people to take me seriously so I felt like numbers meant legitimacy but now I'm kind of just like, I'll post whatever I want to post. Because, when there's like a feature or a beautiful image that I like that features my clothes I'll post it. But then I also use my Instagram stories as documentation of my day and the little mundane things that I find interesting. Like, I have this series of trash bags that I see. I didn't realize they were so prolific, that they were everywhere. Or like, carry out bags. I just think it's so beautiful that like, a weird green carryout bag with like, Thank You on it. And then there's a guy—it's so funny, like, it's a bag right, and bags aren't for guys quote unquote. And I'll see construction workers carrying like, two carry out bags and one is hot pink and one is green and they're carrying them. And it's so funny because that to me is so feminine and so beautiful and like, that's such a great bag even though it's plastic and you're gonna throw it away. If that bag was leather with Swarovski crystals, would you have an issue carrying it? I don't know. I think about that. So I'll post like, I'll sneak a video of the guy carrying a pink grocery bag and it'll be grainy and fuzzy and I'll post it to my story. And like, that's also an expression of my work in a way. I think it's beautiful and I post it, and that's it, without me having to explain anything. I don't explain anything. But that's kind of what goes on in my head.

JD: That's great. Also I love plastic bags! I have a huge obsession with plastic bags.

CJR: I love them. I like carry out, I just love that shit.

JD: I can—I—yes. [laughs.]

[End of interview]

christopherjohnrogers.com

instagram.com/christopherjohnrogers

Christopher John Rogers (CJR): Of course.

JD: I’d like to start at the beginning, and I feel like, this means Buchanan Elementary in Baton Rouge, Louisiana.

CJR: Yeah.

JD: Yeah? Would you agree?

CJR: Yeah, for sure.

JD: So can you speak a little bit about how this path got started, what about Buchanan Elementary spurred this, or if anything in school actually did, or if it was more, like, outside?

CJR: I think like—it’s interesting because obviously in the moment I wasn’t thinking about my future, but I’m really thankful to my parents for putting me in an environment that was, literally, so diverse, from kindergarten.

JD: You mean Buchanan?

CJR: Yeah, school. And that impacts the way I view references. The way that I, like, interact with people, who I feel comfortable around. Like if a space is too white or too one thing, I can’t, don’t feel comfortable. I have to have a bunch of different types of people around me. And like, cultural influences—I have a bunch of different kinds of—I really draw from mid-century art, Dadaism. I feel like that range of references was sparked by going to school with a bunch of different kinds of people. So obviously that was that, and then, I moved schools, to Brookstown.

JD: Oh, I didn’t realize. When?

CJR: I can’t even remember.

JD: [laughs.]

CJR: So I moved schools around first or second grade. I went to school there but, I don’t think they had like, a Talented [Arts] Program. So I went there it was really cool, met a bunch of cool kids and then I moved school. I was so upset, because I like enjoyed myself so much. And so they dragged me out of this school kicking and screaming and I was like oh my god I don't wanna leave and we basically toured this other school that was similar. I was in enrolled in actual art classes, I like, took painting, drawing. It was like two or three days in class they would take me out of class. And I would learn how to sketch and all that stuff. That was like second grade up until fifth grade, elementary school. And, around fifth grade when Project Runway came out. And I was like, what is—I was just like, on TV watching a bunch of shit I wasn’t supposed to watch, a bunch of adult shows, and there was this dark room, and I was like what is happening. I just saw amazing things coming from behind a scrim. And I didn’t even know what that was. In fourth grade, I was always into like anime, manga, cartoons, comic books. I would always draw comics. My friend Katherine was like, why are they always wearing the same thing, you should switch it up. But like, Ash Ketchum and all these people wore the same outfit, why would I change the outfit? But I like, explored it and it was fun, making these characters—how little details could automatically change how you perceived the characters. The more I sketched the clothes the more interesting I thought that was, and my experiences being execute what I had in my head, from like second grade on, influenced how seriously my peers and my teachers took what I was drawing. They were like, oh okay you’re doing this and you’re doing this a lot. So I was like, okay this is what I’m doing. I was looking up different schools in elementary schools like Parsons [School of Design], FIT [Fashion Institute of Technology], SCAD [Savannah College of Arts and Design], CSM [Central Saint Martins College of Art and Design].

JD: Wow, already?

CJR: Yeah just because I was like, "how are people doing this?" So that was kind of like, how it started, went to middle school, just kept drawing different things, and making mini-collections and everyone was like, you're still drawing this. And I don't know, it just became a thing.

JD: The anime—you mentioned Ash Ketchum, which is Pokemon. So I remember the three big ones, Pokemon—

CJR: Digimon.

JD: And Sailor Moon, I guess?

CJR: Oh my god, Sailor Moon was my everything. Tokyo Mew Mew—any sort of like, ultra-feminine but still badass. Misty was great. Anyone playing tech-in, or video games, I was always the girl. I think a lot of gay men, or queer people can identify with that—like, being able to identify as someone else. Being able to be someone that doesn't have to be a stereotypical version of what a girl would be, or what someone else would be. And so, I mean, at that point I was playing games. But looking back, I'm like maybe that was a reason.

JD: Yeah.

CJR: And even in my work now, I think a lot of young, emerging designers—designers of my age—are kind of doing a lot of very—I hate the word unisex, but unisex clothes or clothes that can be worn by either gender that can seem a bit more, like distressed or purposefully ambiguous and in my work I think I try—it just happens to be very very feminine. But it doesn't mean that it's exclusively like, okay for women to wear it, or branded as women's wear. I try not to brand it like that—I just make clothes. And they're feminine, and if you're a guy, or a girl, or somewhere in between, or whoever, you can wear the clothes.

JD: I think we'll unpack that a little bit more in a bit, but let's continue with these formative years for a bit. But before you got out of Baton Rouge, was there anything else that really—teachers that you remember—like, in Glasgow [Middle School], I specifically remember that Ms. Geeta Dave said you were going to be a fashion designer after she saw your drawings. And so I guess, did anyone or anything particularly influence you?

CJR: I mean yeah, Ms. Dave, she was amazing. She was a really—it was weird, because honestly, like during school, I kind of didn't know if I liked her or not. There were days when I loved her, but there were days when I was like, I don't like you. But I think she also was like, really really hard on the students that she liked or people that she thought were talented. Like, she would be like this is a shitty project, why are you turning this in. And at the time I was like, she's attacking me, but it wasn't her attacking me, it was her seeing something in me and trying to push me.

JD: Yeah.

CJR: So I think, that was something. And I also kind of was like, she thinks it's shitty, I need to make it better. And I was actually getting better at the projects she was assigning me. And honestly, I was just really lucky to go to really good schools where I could be myself, like, dress kind of the way I wanted to dress, a little bit but with uniforms. We could always like, wear a jacket or do something weird.

JD: In [Baton Rouge Magnet] High School we didn't have any uniforms.

CJR: Exactly, and that was also interesting, like—Mr. Hotard was the art teacher. Like, all of my art teachers were so different. I can't remember her name in elementary school—

JD: Ms.Trish?

CJR: Yes. Oh my god, you're so good. Okay, yes, Ms. Trish was sensitive, she was really supportive, she kind of saw where each student was going and allowed and pushed them to do that while also exploring the basics of art. I always thought all of my art teachers were really good. Like, they paid attention to the students and the classes weren't huge so they could give us individual attention.

JD: Anyone who wasn't an art teacher?

CJR: Honestly, I think that, who taught calculus—

JD: I know who you're talking about.

CJR: Anyway, the calculus teacher, she was always really supportive. She would see me sketching the margins of like, equations or like whatever and she would come over and be like "this is really good, I want you to design me something." Like, every teacher that knew that I liked fashion and I was serious about it was like, oh you're going to design my wedding dress one day, you're going to do this. It was never like, stop doing that. It was never like—it always really supportive words. I think every teacher was like—I was kind of knew I was gonna do it and they're like, okay you're gonna do it. And that was it. I will say, also a lot of my really close friends in middle and high school, like my best friend Julie Liu. In elementary school we were really good friends and we would sketch together and figure out what we liked. In high school we did our first fashion show together, where we went vintage shopping. We didn't know how to sew at that point, but I was like, I have to do this fashion show because it was the first time I could put something out. That my voice—our voice. So we just went vintage shopping, took things apart and resewed them back together which is kind of like, the classic story of how people start making things.

JD: When was that?

CJR: My sophomore year.

JD: And you just put on a fashion show?

CJR: Well Brianna Harris actually organized it. And she knew how to sew, her mom was a seamstress I think. She made patterns, she fit everything to models, like, it was very professional. Her show was the last one, and it was like, it was beautiful, actually. I think our energy—this feels so bad to say—the frantic "we need to do this" that kind of body of work was received really well. It was so funny because after showed, like, everyone kind of left the auditorium. But we were like, wait, it's not done, the show's not done.

JD: Oh no!

CJR: So I felt really bad but it was interesting how people saw that as kind of like, a moment. But also even the way that she, and our friends from McKinley [High School], they all dressed alike and I hadn't seen that before. We didn't have money to like, buy Abercrombie or whatever so they went thrifting and bought dresses and cut them really short, and wore heels to school. It wasn't sexualized that they were wearing these clothes. They were kind of like we like this proportion, this looks good, this is me at the moment. Our parents were always like, what are you doing, you're wearing things that are too short or too loud. It was never about getting anyone's attention, it was about being ourselves finally, exploring clothes as expression, color as expression. And maybe bending the rules because they didn't make sense. Like, why could guys get away with a shorter short than a girl could. Why was that a distraction? And if was a distraction, can we talk about why it's a distraction and get to the root of the problem? As opposed to changing the way that people are dressing. And so that—those are still things that I try to unpack. Like, why should this person wear this, why can't they wear this. You know, and it's like, is the fact that when they do wear it, why is a shock? Should it continue to be a shock? Just all these things, that kind of influenced, and still influences the way that I make clothes.

JD: So these are all thoughts that you had in high school.

CJR: Yeah, this, and also trying to get through the math test. But also in the morning, there are so many things that I could wear. And also looking back, it's a very Southern thing to want to look nice.

JD: What do you mean by that?

CJR: I guess I'm jumping ahead, because I like to make connections with random things but, thinking about people that make clothes now [inaudible]. They make things that are a bit more distressed and maybe not so perfect. It doesn't seem that the point of the clothes is to be perfect. But when I work, I always try to think of like, both of those things. So being Black and being from the South, at least in my family, in my experience—whenever you leave the house, make sure you look like you have an address. Look nice, present yourself, don't get in trouble, blah blah blah. So whenever I saw everyone wearing jeans with holes, I was like, oh maybe I should try that out for myself. My mom was like, you're not doing that. If something was a little bit off, she's like, it doesn't fit right or this color doesn't match. My grandma always wore head-to-toe, like a color head-to-toe green, head-to-toe red, matchy, church lady. And that's also something that I bring into my work. Whenever I shoot a look, I love the visual tonality of a monochromatic look, I think it's effective and it's about the color and the emotion of that color. I also like hems to be perfect, I like things like that, but also the franticness of me and Julie doing that first collection, where hems were ripped and things kind of didn't match, things kind of off—me analyzing why a hem has to be perfect, trying to get to this perfect moment allowing the imperfection to be part of the design, and like, the equilibrium and exploration of that process is interesting to me. So I like for things to reach, or like, grow towards perfection but the process is also part of the work in a way, and should be reflected in the final result.

JD: And you also made things for people.

CJR: I was making things for Julie—again, we didn't even know what the fuck we were doing. Like the day of prom, everyone was looking nice and Julie was like, I'm not about to buy a $300 dress. And I remember at one point she thrifted something and we kind of just wrapped a bunch of fabric around her, and like, that was a look. And as she was dancing, it was coming apart—we were just having fun! It was just so funny.

JD: Wait, what thrift shops?

CJR: It was like, America's Thrift. This was when we had cars at some point so, we were going to Goodwill, the first one we went to was like, Happy Tuesday. I remember we would go and stuff wasn't cheap. It wasn't expensive, but it wasn't cheap. A jacket was like, ten dollars, which is like not bad now, but back then we were like, oh my god, ten dollars stop! So we went to cheaper places and bought shit and safety pin things and sewed things. Again, it was like we were trying to make it look great, but we have to put a safety pin in it, because we don't know what we're doing. So it was part of the work as well.

JD: So then, you went onto further education. I remember you did get into Parsons—but you ended up going to Savannah College of Arts and Design. Why did you pick SCAD over, I'm sure you got into other schools as well?

CJR: So the schools I applied to, I got into Parsons Early Action, I got into FIT Early Action. But I didn't get my Parsons acceptance letter until May. I got accepted early but they didn't email my acceptance letter. And if I had accepted it, I probably could have gotten scholarships and might have probably had more of an opportunity to go to Parsons, but at that point, we hadn't heard back yet, so we were like maybe I didn't get in, maybe I didn't get a scholarship, so that was kind of out of the options pile. And then, again, my friend Brianna went to SCAD for her first two years, and then moved back to Baton Rouge. But they were like, oh she's going there, it's a good school, maybe she can look after you in a way. You know, my parents were very like—no one ever really leaves Louisiana, or Baton Rouge. So, it's like, you're leaving, we don't want you to go to New York, we can't monitor you. SCAD's closer, they gave me a good scholarship, they went and did the whole persuasion thing and took everyone around and showed the best buildings and they had like, a lunch for everyone that was really fancy for the prospective students. So my parents were like, "this is great, you'll love it." I always knew, like I'm going to go to New York. Like, where else would I go? Or I'm going to like, London. Where else would I go. And I ended up going to SCAD. Me and my friends were actually talking about this yesterday, and we were really happy that we went. Because I think that I was able to really find my voice in a place that was more adjacent to the art world than Baton Rouge, but also not so crazy and hectic like New York. I also wasn't influenced by New York expectations about what kind of design I should do. The work was still about kind of like, a Southern point of view. I never considered myself Southern, or Louisianan. It was kind of like, I am me I live here. Especially having the internet, LiveJournal, Tumblr, Facebook, MySpace. You could look at people—even this website called LookBook, which Julie and I tried to do for a little bit—you could see people's stuff from all over the world, you could like, talk to people in Denmark and Morocco, wherever. Like, looking back, it's so funny how—even like, the debutante moment—which, I mean I never went to any debutante cotillion balls or anything. It's about kind of like, looking at people who are doing those things—it's so weird to me that that was a thing but also like, being inspired by the looks. The Mardi Gras balls that I never got invited to, but you would see people looking fancy. So that was kind of like, oh maybe is that something that I desire, is that something I want to participate in? But then also looking at my friends who were playing soccer, or like, how Julie would wear like, a corset to school with like, flat shoes. Or like, a fancy satin skirt with a tank top. And that mix of like, I don't care but I also care. Um—what were we talking about?

Baton Rouge Magnet High Fashion Show, “Rogersliu” photoshoot, 2009. Courtesy of Christopher John Rogers.

CJR: So that, I was able to explore those things without having to think about like, Black and White New York, or like, practicality. I didn't really start thinking about pragmatism in my work until I moved here. Because then I was like, oh I have to walk everywhere. Or oh, you can't wear heels everywhere. Or you can't wear a boot everywhere because you're gonna die.

JD: [laughs.]

CJR: You know? So, I was really able to explore the aspirational part of my work in school.

JD: So what was it like? What was SCAD like?

CJR: SCAD was um, really, slow? It was a good experience in retrospect, but there I was like, this is so slow what am I doing?

JD: What do you mean by slow?

CJR: It didn't have what I expected from a college experience. It was different than what I expected. It was, it felt very like, hometown-y. I feel like it's New Orleans mixed with Baton Rouge, but like—I don't know. It was really weird. It was like, house parties were—it was really weird. You have to go. Savannah's like really weird. It's like—I don't know. I was actually really focused on work. I also was a goody-goody. Coming from school, with my parents, I was like don't do drugs, don't drink. I didn't have a fake ID so I was scared about getting caught, so freshman year, sophomore year—I didn't have a fake ID. I only started really going out when I was twenty-one, in junior year, so everyone had already, like, fizzled out. They were like normal, and I was like whoo! Going crazy. So the first few years were like me working, taking it slow, going to the park. There wasn't a lot of things to do besides work and hanging out with friends, so it was kind of chill, kind of slow. Maybe if I had gone to New York, I would have tried to sneak into clubs, and do all that stuff. Because like, there weren't that many clubs to sneak into in Savannah, you just kind of like, walked around.

JD: Well, why don't you talk about the work for a little, the work that you were doing? What was your major? What was the education process like?

CJR: So my major was fashion design.

JD: Oh okay. [laughs.]

CJR: Yeah, and we took like foundation courses basically the first year. Drawing, blah blah blah. I was like, really bored, because I had already taken those classes from like, second grade. Like, basic drawing classes to color theory, which I love, I love that class. But having to mix colors, and like, a lot of tedious work and it wasn't fashion. I really wanted to learn how to sew properly. I wanted to learn how to make the ideas in my head come to life in a way that was real and tangible for people. So it was kind of frustrating to have to like, take all these basic classes. Well also not being able to do anything else, you know what I mean? So it was a lot of time just like, making friends and doing things outside of class. I would also do stuff last minute, and do it really well, and like, present it and be like, this is it, and everyone was like oh my god this is so good! But like yeah, because I've already done it before. But like, yeah that was that. Around the end of my freshman year, I finally took my first sewing class, which was just the basics, which I already kind of new a lot about, but I learned a few things, which was cool. Then, sophomore year, I was always kind of jumping ahead of the curve because I was so impatient. So I was always like, what classes do I actually need to take to be able to take my first real fashion class. And then, one was like, an apparel one, which is when you make, you drape a bunch of things and then you make one dress. So everyone was making like a basic, you know, little shift dress because this was our first time exploring the form. Then I was like, how complex can I make this. I wanted to make a jacket, I wanted to make pants, I wanted to do all this stuff, and then my professor, who is one of my favorite professors at SCAD now—then, I hated—I really did not like her while I was taking the class. I was like, oh, I've shown collections in New Orleans, I've done all this stuff, and she was like, I don't care. Looking back it was like, who cares, you know. But me, being like eighteen, nineteen, I was like, look, I'm doing cool stuff, and she was not impressed. She didn't care. I was really mad because I was like, why am I not impressing you because I'm trying to do everything that I can, but it wasn't about what you had done before. It was what are you trying to do now, in a way. She would really push me to not do what I thought that I could do to do more. She was like, if you're so good, then show me. At that point, I was turning in things that I thought were good, but then she gave me like a D and an F and I was like oh my god, I cannot fail this class. So, I would go every day and every night, even when I wasn't supposed to, and like, perfecting everything that I was doing and like, it was senior time. So, professors work with freshmen, all the way through senior, it's the same professor. So she was teaching her senior class, which is like senior thesis: huge body of work, crazy forms, all these things. So then I was looking at seniors but I was also doing my own crazy thing and they were kind of annoyed at me because they were like, why is this sophomore here when I have professor time because they don't get a lot of time with the professor. And [Professor] Satchi was like you're annoying me, you're annoying me, and I was like, I don't care, I need you to teach me this. And she kind of liked that because it was like okay—like the Ms. Dave thing. And so then I learned if you want something you really have to like, you can't think that you're special. It really humbled me a lot and I was like, thank you for that because there are so many people who want it, so you have to show that you want it. So I learned that from her.

JD: Who is she?