Sophia Michahelles & Alex Kahn

Co-founders, Processional Arts Workshop

Conducted by Lauren Drapala on November 4, 2019 at Red Hook, New York

Sophia Michahelles (left) and Alex Kahn (right) at their home and workshop at Rokeby Farms in Red Hook, New York, November 4, 2019. Photo by Lauren Drapala.

Sophia Michahelles began her career as a maker and performer by creating set designs and puppetry for theatrical productions at McGill University. She is also a performer with Basil Twist’s Obie-award winning Symphonie Fantastique and has created and performed solo puppet shows, including Georgette's Debut, her one-woman drag burlesque of George Bush. Alex Kahn is a visual artist whose work draws on his cross-disciplinary background in theatrical design, printmaking and digital arts, sculptural installation, and pageant puppetry. He previously served as the Technical Director at the NYC-based Kitchen Performance Center (c. 1990–1993), chaired the Printmaking Department at the Maine College of Art (2000–2004) and continues to maintain an independent practice as a theatrical designer, printmaker, installation artist, and teacher.

In this interview, Sophia Michahelles and Alex Kahn describe their career to date working together at the intersection of puppetry, community, performance, and public space. They discuss their work with New York's Village Halloween Parade (New York, New York, 1998–present), Pageant Puppetry Workshop and Midsummer Procession (Morinesio, Italy, 2002–present), Ebune: A West African Rite of Spring (Museum of African Culture, Portland, Maine, 2003–2004), Commute of the Species (Katonah Museum, New York, New York to Katonah, New York, 2010), The Black Cat Committee: A Kiev Puppetscape, Andriyivskyy Descent Kiev, Ukraine, 2011), Odysseus at Hell Gate (Socrates Sculpture Park, Long Island City, New York, 2011), Morningside Lights (Harlem, New York, 2012–present), The Architectural League's Beaux Arts Ball (69th Regiment Armory, New York, New York, 2013), Procession of Confessions (PEN World Voices, New York, New York 2014) and WHIRL: The Worlds of Robert Chanler (Vizcaya Museum and Gardens, Miami, Florida, 2016).

Interview duration: 1 hour and 58 minutes.

Lauren Drapala (LD): It's November 4, 2019, and I am Lauren Drapala from the Bard Graduate Center sitting with Sophia and Alex at their workshop at Rokeby Farms in Red Hook, New York. I wanted to start with a general question for the both of you. How would each of you describe the Processional Arts Workshop?

Sophia Michahelles (SM): Do you want to go first?

Alex Kahn (AK): Um, no. [laughs.] We are a small nonprofit, ever-shifting ensemble of artists, and our mission is to create site specific human-powered and community-built performances in public spaces that work within the framework of the tradition of processions, parades and Carnivalesque performances.

LD: [to SM] Would you like to add anything to that?

SM: No, I think that was actually an excellent definition.

LD: As a follow up to that, how do each of you describe your roles within this group?

SM: We do work very closely together. I mean, I think there are certain aspects of the work that we might take on, but I think that over the years we really have gotten very good at kind of figuring out, "Okay, Alex is taking this on—I'll take this other aspect on." And that applies to aspects of design, or aspects of just production, or even within the context of a public workshop: scanning the room and seeing, "Alex is on that side of the room—I'll go to that side of the room." I think that there are there are things that we tend to gravitate towards and we know each other's styles. We've been working together for twenty-one years and not all collaborators work this way, but I think that we tend to approach things in not radically dissimilar ways and then, from the inside out, work out who does what.

LD: Can you talk about some of those places that you tend to gravitate?

SM: I would say Alex is very good at having the first story—the basic idea of a story. I think I tend to think more in images and Alex is really good at thinking about things in terms of a narrative. It could be a more formed thing, but sometimes it's just the first idea, and then we will work out images together. Does that seem—

AK: We could also look at it as a form and content kind of shift where narrative—another way of saying, that is—the conceptual framework of what are we going to do. We come into a historic house or into an urban situation and we both do a fair amount of research. But, then out of that emerges this sort of like condensed mobile story that we're going to tell. That's a lot of the content framework. But then there's also the design element. Even within the design, Sophia is more likely to address costuming—working with textile and pattern and design. I will gravitate more towards structural design and sculptural design.

SM: And lighting.

AK: And lighting. Lighting and projection, and stuff like that. But then there's a lot of places those areas intersect. I mean, if you're talking about a costume that's fifteen feet tall, then there's going to be a structural component to the textile element. Inversely, you could possibly have an element of design that's built into something that is structural in terms of how the infrastructure shows through in a lighting context and things like that. So, it's quite cross-pollinated in a lot of ways and when we sit down with an actual conceptual design, we sort of naturally delegate within that given year's framework, or that given performance's framework, to one place or another.

SM: And sometimes the delegation is more—I will take on these creatures or this aspect of the design, and you [speaking to AK] will take on this other one. And sometimes it's more, like, I'll take on this component of this ensemble. [...] There can be clearer places to separate and sometimes it really is "I'll work on this aspect of a body and you'll work on this other aspect of a body."

AK: There is also a huge human element to all of this. I mean, when we talk about this kind of work, the first entry point for a lot of people is the materials, the methods, the technologies that we're using. And that is a big part of it. But none of that means anything unless if you're talking about a performance that has sixty to a hundred people in it. None of that means anything until you have bodies that are actually animating these things. The human engineering is a huge part of this. How do you talk to people? How do you bring volunteers into the process? How do you direct non-professional performers? How do you create a performance where you only have one brief rehearsal or no rehearsal? In some contexts. We've also delegated in that area as well where Sophia does a lot more of the one-on-one coordination of volunteers—talking to people, figuring out where they're going to be comfortable. Are they bringing kids along with them in this procession? Is there a role for them to play? What happens if they miss a rehearsal? Can they still be in the final performance or do they have to switch places with somebody? All of that, like, one-on-one, making people feel welcomed and respected in the process—that's very much Sophia's area of expertise. I am often more comfortable, once we're actually all there and people are in their costumes or puppets or visual elements, to address a large group in as concise a way I can, and actually direct a performance so that they end up doing the thing that we want them to do. But you know, if you have the wrong people, or not the right number of people, or people who aren't actually going to see it through to performance, the direction doesn't mean anything either. You have to have, at that point, the groundwork that goes into preparing people for the kind of commitment that they're going to undertake.

LD: So, I guess along those lines, is there a typical organizational structure in place when you take on a project? You've outlined the roles that both of you play, but are there other people that are consistently involved?

AK: It's very interesting over the years because, there have been people we've hired on occasion or people who come and will volunteer for a solid month. Like, for Halloween, we have one person who comes from England, who is a professional costumer, teaches performance design and by any standard is a total professional. And basically, she just loves the Halloween Parade [New York City's Village Halloween Parade] and she wants to be a part of that looser, haphazard design: last-minute stuff that happens when we're doing this grass roots, giant performance kind of thing. I think she gets a lot out of that.

AK: That's Kate Whitehead, who you can interview if you want. She's here. She takes on a kind of leadership role. We come up with the basic concept, for example, for Halloween. And then she is very much an implementer of large swaths of that and helps direct the volunteers and helps basically organize the whole thing and does a lot of tech support and all of that. Beyond that level, we basically have what's what in acting would be called an ensemble cast. There are probably fifteen or twenty people who have just volunteered to puppeteer year after year, after year, after year. Some of them ten, fifteen years come back every year—not just for the Halloween Parade, but for other New York area things that we do. Some of them have taken our workshop in Italy and have come there to do work with us. And that allows us to do so much more, because you don't know if somebody has just signed up on a forum and says, "I want to carry a giant fifteen-foot tall white rabbit puppet"—you don't know if they really know what they're getting into, if they can do it. Whereas, if it's Albert Melendez, "oh, that's Albert. We know he can do it. We know he will follow directions. We know he will be precise in this certain way. We know that he will take this role on in a different way from, say, Alex Bratcher, who will bring an impromptu energy to it, but is not so much like following the note-for-note instructions." And within an ensemble cast, you can plug people into different roles where more or less improvisation is going to benefit the overall performance, where you have stronger people and more fragile people, more graceful people and more just purely physical people. And we've gotten to know these volunteers over the years so that when we start casting things in the overall performance. We at least know that key positions are going to have some people in each position who are absolutely solid.

SM: And, I would say that this is true for the Halloween Parade and other projects that we do in and around New York City, because we have developed this amazing group of performers and people who come and help build projects—who come to the public workshops. But it's not the case when we do many other projects where we go to a new place. And so it does allow us to be more ambitious in our designs—certainly in the Halloween Parade, where we can take risks that we might not take if it's a first time event in Houston or Miami. When we go to new places, we know that we might not know anyone there, but we know that through the process of the public workshops, which will typically take place ten days previous to the event, we will also learn more about people there. People might initially come in and say, "Oh, I'm not a performer," or, "I just want help papier mâché" or whatever. And then, they'll get involved in the story and in the performance and realize, "Well, I'm performing, but I'm performing by carrying a lantern or by being an arm of the puppet. I don't have to go and speak to a crowd." They can be part of the thing or they're in a mask, or you know, some people who may not be performers, feel comfortable with this. And then people who are performers can jump in and be part of a more impromptu performance that doesn't require months of rehearsal or that kind of thing. So, we are still able to kind of figure out who the cast is in places where we are new. Relating to that—I think this was part of your initial question—when we do projects in new places, but also in the Halloween Parade, having a volunteer coordinator, having someone who's not us—who is tracking who's coming to the workshops, who's coming to a rehearsal, communicating with all the volunteers—is critical because we don't have time to do it while we're in the midst of a project. We can work with someone and sort of oversee what the information coming in is and what the information going out should be. But because people are such a huge part of the work that we do, it is really important for someone to be that communicator because we can't. We can't build at the scale that we build and we can't perform on the scale that we perform without someone really tracking and making sure people show up at the right time and know what to expect and feel welcome.

LD: That makes a lot of sense.

AK: We also work—among the volunteers—with a whole structure of captains. Almost everything we do is done in multiples. To have an impact on the street, you can't have one mask walking down the middle of the street. You've seen the Halloween Parade and it just wouldn't show up. So it's sort of like, "Oh, we like this character. Okay. Make twenty of them." And once you designate a captain or two captains of that section, it's much easier to communicate subtleties of a performance to one person and direct them individually and then have them direct just their group. And then, they don't have to worry about anything else. They can just focus on their posse of leaf masks, or Max characters or whatever—you know, from this year's Halloween Parade. Those are some of the masked characters that we had. And that way the dissemination of information is much more streamlined, because talking to one hundred people all at once, you have varying degrees of attentiveness. You don't know if you're really getting through. Nobody has an opportunity to ask questions back. But, if there's a captain, there's a lot more interchange, and they also learn things as a micro ensemble within the larger ensemble that they can experiment with. They can come back and say, "Hey, we have this idea if we all turn our heads to the right and then beat the drum—does that work for you?" "Oh, yes, that's great." So they're going to put more time into their performance than we could because that's all they have to worry about. That actually extends even to the building process. We've often had situations where, you know, there were elements that needed final painting. And if it were up to us, we would take ten to fifteen minutes to paint each element and just get it done. There's twenty of them. We don't have the time. There's other things that are prioritized. But if you hand those elements to twenty different people and say, this is all you need to do today, you're going to get one person who's going to spend six to eight hours painting this thing. So when we did these Day of the Dead skeletons in tandem with a Haitian artist [Didier Civil] in 2010, we did something like that. We carefully selected who had the painting skills to carry this on. But the level of detail and the level of originality and uniqueness within each particular skeleton head that we gave them was stunning. You know, if it had been up to us, we would have done a sort of generic, you know, throw a couple of decorations on it, it's done, which has its own charms in terms of the immediacy of scenic painting. But sometimes it's really nice to be able to say to somebody, "you can just lose yourself in this process for an entire day." And at the end of the day, we'll have something that's a real work of art that comes out of it.

SM: Along with the idea of creating multiples, there are a few lessons we've learned over the years. One is that you can come up with a formula and easily teach it to a group of volunteers. Referring back to this year's Halloween Parade performance—we had ten leaf-men heads and there was a way of doing them, and it was an easier thing to teach a group of volunteers than, say, figure one out: "okay, that looks good. Great, okay, we did that one. Let's do this totally different thing." It doesn't lend itself to delegation. So, that idea of repetition works well if you're working with volunteers and then translates really well to performance because it owns the street in a different way than a single mask or a single puppet would do. But, the other thing that it does is if there's a group of people doing something, they're never going to be doing exactly the same thing. So they're all going to have personalities within sameness. And that's something, that if we were making all of the leaf-men, or all of the skeleton heads or whatever, it would be just the two of us. Both of our ways of painting, or our ways of sculpting would kind of be repetitive, whereas if you have a group of people, then you have this wonderful synergy because they're all doing something similar, but they all bring a slightly different style to them. That's something that's very important to us, and sometimes, for some projects, that is key. There is a lantern procession that we do in Morningside Park in New York City called Morningside Lights, which we started in collaboration with Columbia University's Arts Initiative and Miller Theater. It's a lantern procession that starts in Morningside Park and ends up on campus, and each year we develop a theme and for that project—we don't design anything. We really design the concept and we teach people the techniques. The techniques change year by year, where, the way that we built the lanterns will change depending on what it is that we're making. But, the individual designs are open to the people who come to the workshop. And so this year, for example, we did "Island," and it was part of a larger theme of the year for water on campus at Columbia this year, but also, you know, for us it was a way of looking at climate change and sort of looking at this idea of rising sea levels and the fact that islands are often the ones that are at the forefront of the reality of climate change. And the larger idea of isolation, that, as humans we may be going through it now. There are all sorts of entry points. We would have focused exclusively on that, whereas when we were opening it up to the public. Some people got really excited about that as a subtext and worked with lanterns that address that. But, other people had totally different approaches. I don't remember how many lanterns we made, but it was sort of an archipelago of about fifty: many large and then some smaller ones. Collectively, there were totally different, totally different concerns. And so, to us, the idea of working with large groups of people—sometimes we really focus on this idea of multiples, but sometimes we really look at the idea of multiples opening up to individual interpretation, which is beyond the capacity of two people, to invent many. How many versions of this can we come up with? You end up as an artist being stuck in certain ways of seeing things, and this allows us to come up with an idea and see where it goes.

AK: In a way, it imparts a kind of art of curation. We're setting up an intellectual framework. Think about the mythology and the history and the legacy of what islands mean to us as humans. And that could be mythological. It can be historical. It can be from literature, you know, countless references. And, by creating that conduit for other people's creativity, who are essentially creating a curated show. But, that curation ends up being collectively a different kind of distributed authorship underneath one larger authorship of processional arts. So, it's an interesting thing because in talking about contemporary art, people often have interesting questions around what is the nature of authorship in this day and age. Sol Lewitt sort of broke that open with creating formulas for other people to make his drawings. Certainly Jeff Koons, as you know, has a factory that makes his work. But, in a more interesting sense, there are people like Mark Dion who will do these community interactive pieces where they'll dredge stuff out of the Thames River and with the community build a museum. It's all Mark Dion when he does that. I mean, he is the overseer of a broader concept, but he's not just allowing people to participate in the making of his work. He needs them to be reflected in that work, because the work is a reflection of the people who are participating. So, you know, it breaks down some of these ideas of authorship that exist in the fine art world and starts to be maybe more relevant to the way art making works in other parts of the world or in the craft world or things like that, where there is this distributed sense of collective making. And that's something we think about a lot. Often, community artists are sort of kind of classed as—"Oh, well, you're doing this good thing for a group of kids in some underserved neighborhood, but it's not really art because you're allowing a bunch of eight year olds to make your work." And our whole thing is like, "No, by harnessing their energies and channeling it in a way that has integrity and specificity, you're making work you could not have made yourself. You're creating a work that would otherwise not be able to exist." And it's not in any way secondary to the quality of the lone artist in his garret studio, making the master painting in the modernist paradigm. So for us, we consider ourselves very much in that contemporary mold of challenging—where does the authorship happen in a work? And even in our own work, as Sophia was saying, there's a sliding scale. So, for Halloween, we'll work out conceptual drawings from the very beginning because there's a particular vision. It's a commission for the parade. It has to happen in a certain way, although there's many avenues for creativity that volunteers will bring into that. And then, for something like Morningside Lights, like it really is much more about just harnessing the imaginations of fifty to a hundred people and making that, their imaginations, part of what we're revealing. What is the shared perspective on a given theme that people bring in and how can we make that physically manifest?

LD: Well, thank you. In many ways you have both brought up so many interesting points that have been consistent threads throughout this course [Craft and Design in the USA, 1945-Present, Bard Graduate Center, taught by professor Catherine Whalen]. And it leads perfectly to my next question. Do you find it productive to think of your work within the broader fields of fine art, craft, or design?

AK: I think it's useful to the point that it's useful and then it has to be jettisoned when it's no longer useful. You know, in the sense that, if we aspire to be spoken of in the same circles as practicing contemporary performance artists who come out of the kind of MFA-world and the gallery world, you know, you can sort of bristle at, "why aren't we considered in that same breath?" But at the same time, you step back from it and say, "well, we're sort of like that. We're also not really in the puppetry world either." The puppetry world doesn't really acknowledge what we do in the same circles as, say, practicing on-stage puppeteers would, because we're not doing staged works. We're not doing proscenium stage puppet narratives over the course of a ninety-minute thing. We're partly in the Carnival world. So, when we went to Trinidad on a Fulbright in 2006 and people asked, "what do you do? What's your practice?" We were able, for once in our lives, to say, "well, we do mas," which is the Trinidadian term for the masquerade, that is that one of the three key components of Carnival in Trinidad, the other two being calypso and steel band. But, you know, we said, "we do mas" and they're like, "oh, okay, we understand what that is." Because the masquerade bands in Trinidad largely do similar work to what we do in terms of having many, many people in mass costume, body extension. Less puppetry, but there is some aspect of animatronic symbols like that that they bring in. And, these huge king and queen costumes. They immediately knew what we were because we fit into a genre that they grasped. So, I say that it's useful in the sense that we have applied for things and been involved with communities of makers based on our ability to masquerade as one thing or another, depending on who is doing the funding and the supporting. So, if the grant, for example, is like, "we support community-based artists," we're community-based artists. If the grant is "we're looking for visual artists," well, we're sculptors. It's just that our sculptures and 3-D designs happen in the context of wearable art moving through public space. You know, "we only support puppeteers." Well, sure, we're basically puppeteers, but we do puppets on the street as opposed to being on the stage. So, it helps to be a little bit flexible and versatile in terms of your self-definitions. The reality is that we exist in a kind of niche of a gestalt practice that brings in all of those different things, which is why when we had to choose a name for our nonprofit and we find all kinds of creative names and fun names. And there are some wonderful things that kind of came through that brainstorming process. In the end, we were like, "nobody has ever really used the term processional art as a genre of making." And we feel like that defines what we do, even though it brings in dance, masking, costume, sculpture, projection, sound—you know, all of that stuff. Puppetry. If we can call ourselves Processional Arts Workshop, people will get that processional art is a thing unto itself that has many intersections with other fields, but it really fundamentally is its own way of making. So, we'll pretend that we're any number of things. But in the end of the day, that's what we are.

SM: I will add, on maybe a more personal note, that I really enjoy being at the intersection of many disciplines that other people belong to and the feeling like there aren't that many people that I know of that as contemporary artists do specifically what we do—though there are many people who do things that involve an aspect of what we do. But, it can also be a little lonely. There are moments where I'm like, but I want my community! Usually in the winter. [laughs.] And then, you know, a little while later, I'm actually quite happy that we're creating our own way.

AK: But, there are a few contemporary artists who have done amazing work in processional art and for whom that term would be totally comfortable and familiar. There's one guy we met in Trinidad who has since become kind of global. His name is Marlon Griffiths and he started out designing children's Carnival in Trinidad, which is actually where most of the innovative design happens now, because grown-ups just want to party and have a good time and wear a bikini and beads, and it's a little bit of more of a party culture than an art culture, whereas the children are willing to wear any number of crazy contraptions so that they can be part of the judging process and all that. Anyway, a little background. But, Marlon started designing children's Carnival bands and then left Trinidad. He went on a residency to Japan, where there's also a huge artistic festival tradition and then has now sort of brought Trinidadian postcolonial politics into public spaces as kind of these ceremonial armor pieces that he creates. He's done work in South Africa, at the Tate in London, South Korea. So he's done some amazing work and he's sort of made it something that within the realm of contemporary art, people can talk about and say, "Oh yeah, artists walking in a procession with wearable work that isn't quite costume, that isn't quite sculpture and it manifests itself in a certain way." What I find fascinating is that for him, drawing on the legacy of hundreds of years of Carnival practice is a natural. Like, that's where his sources come from. He worked with this guy, Peter Minshall, who is a legendary Carnival designer, did several Olympic ceremonies, does amazing, dark, challenging work and, you know, with literally thousands of people in his pieces. And when I've seen the contemporary art world in New York attempt to do this—there was a project that was called the Art Parade for a number of years that was run out of Jeffrey Deitch projects. He's since moved on to California and the Art Parade sort of dissipated. But, for the artists who are participating in that, who are all part of the Chelsea Soho art scene, like, "We're doing this crazy thing where art comes out and it does art in the street while it's moving. And oh my God, it's so radical." And the work was, you know, not that interesting. And it was sort of solo people wearing a thing and walking and there was none of that sense of the mass of one hundred people doing a thing at once in a wave. And I was just fascinated because they were uprooted or were separated from their own, what could be, canonical legacy of art history from which they could draw. But, nobody was looking at Trinidadian work or Brazilian work or the work that happens at Fasnacht in Switzerland. They were just looking at other contemporary artists. So it'd be like if you wanted to be, you know, a blues musician, but you could only look at pop music as your source and you'd never heard of John Lee Hooker or Muddy Waters or something like that. Or, if you wanted to be a painter, but had never looked at Matisse or Picasso. They were just separated from this wellspring of amazing work that's done largely namelessly and collectively in a lot of Carnival cultures around the world, but has every bit the same sophistication and complexity and storytelling that any kind of contemporary performance might. So, I'm always interested in how people sort of parlay—like, how do you figure out what your background and what your legacy is? What are you drawing from? A lot of craft artists don't have to worry about that so much because there's often a very established legacy of craft. If you're a potter, there are potters you're going to look at if you are a weaver or textile artist, there are people who are trailblazers in those areas and they tend to sort of know each other's works in a really clear and present way. But if you're talking about parade art, it's not quite as clear and you have to do a little bit more digging to figure out who are my forebears—that, while we're not making work, has been a really important part of our practice. You know, traveling to Trinidad, to Switzerland, to Croatia, to various places, wherever we can, to kind of feed our own practice by looking at people who have really been doing this in some cases literally for thousands of years.

LD: So, that's a perfect segue way to my next question—can you talk about your first collaboration together?

SM: 1998. We worked together on creating a performance for the Halloween Parade. Alex had worked with the previous designers. Debbie Lee Cohen, primarily, but Mark Kindschi and Maya Kanazawa. [Kate Whitehead walks into kitchen] Hi, Kate! Okay. There had been a few years without new work. And then, for the twenty-fifth anniversary of the Halloween Parade [to AK] well, you should tell it. I'm talking about your version of it. But, I came on because Alex had been working on the parade and then I came on to work with him on this design that he had proposed to the director of the parade.

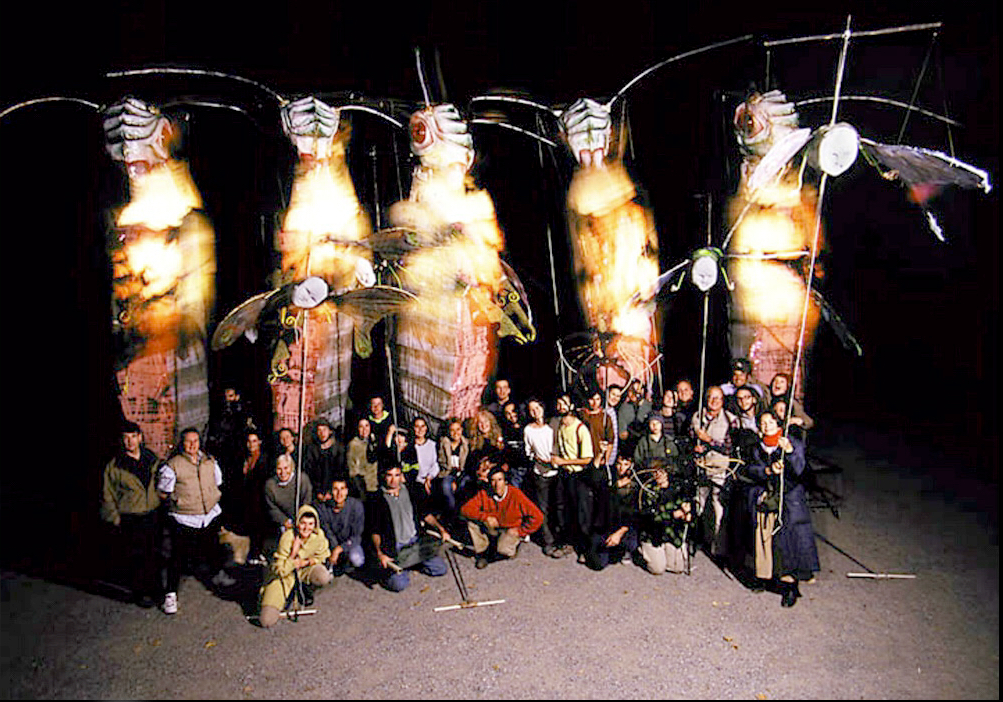

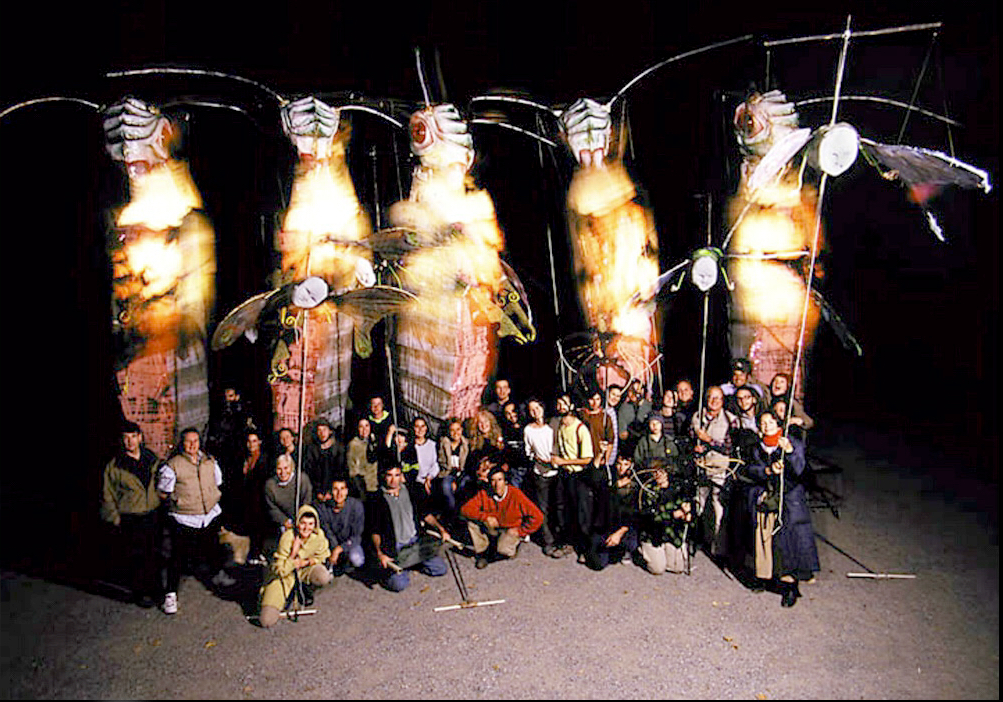

AK: One of the things that happens with parades that have been around for a long time is that people remember the first parade and the second parade and maybe the third parade, and there is a kind of nostalgic—a bittersweet nostalgia, I should say—about where the parade has come since then. Twenty-five years along the Halloween Parade went from being 125 people meandering through Greenwich Village to being a massive thing on Sixth Avenue with over a million spectators and fifty thousand people in costume. So, for a lot of people, it's a little bit like the little puppy grows up into the big dog and you're like, "oh, my God, how are we going to feed this thing?" And it's not cute anymore. So, there was a lot of criticism of the parade. People saying, "Oh, it used to be this beautiful little family-friendly thing and now it's this massive corporate thing." Often people ascribe things to the parade that are not even true. Like, there isn't a wealth of corporate funding. We kind of wish there were, but there isn't. Because it's still a countercultural event and not everybody wants to have their name on it. A lot of people felt that the puppets themselves were a manifestation of its spectacle orientation, that it was no longer an intimate thing. Of course, giant puppets were part of the parade from year one. They were the only thing in the parade year one. So there was a lot of bitterness around the growth of the parade because it wasn't what people remembered that first few years, which I'm sure were magical. I wasn't there. I was six years old. So, we wanted to address that in the twenty-fifth anniversary by saying, "Look, things change. Events are organisms and organisms have a lifecycle. And sometimes they get so big that they can't sustain themselves anymore and they stop. And some times they plateau and become a mature version of themselves. And sometimes hey get small again or they break into many events like Burning Man has many small, Burning Mans that are happening these days." So we just want to acknowledge that, you know, performance. So we thought the best way to do that was through the metaphor of a cocoon, a larva becoming a cocoon, becoming a butterfly. So, we called it Metamorphosis. And we built five giant caterpillars, Luna Moth caterpillars, that were twenty-feet tall and lit from within glowing pink and green. And then at a certain moment in the performance, the idea was that their skins would drop off. It was like a lepidoteral striptease and their skins would come down and there would be these white, filmy moths underneath that suddenly would spread their wings and they had a twenty-, thirty-foot wingspan. And there were five of them in a circle. So, it was a massive circle of basically semi translucent material that then became a shadow stage for these human figures that then themselves spread wings and became sort of insect people that were flying around and taking flight. So this idea is that metamorphosis: yeah, it happens and it leads to new and wondrous things. They were beautiful caterpillars, but their lifecycle came to an end and they became something new and special. So the background of that is, that we started, you know, I started doing the drawings for it in June, maybe in May. We had kind of worked out a design plan. Sophia had done puppetry in her time at McGill and was interested in doing more. So we started working together on these things. But, what's interesting about that year is that not only were we working together, but it was the initiation of our whole public workshop process that became the kind of linchpin of our nonprofit work. So we worked all the way through to the end of August, mid-August, and we were looking at what we had accomplished over basically eight weeks of hard work in the summer with a few volunteers coming in now and then, but mostly just us, and a few people who we hired to do some extra work. But basically at the end of all of that work, we had one prototype that wasn't even really complete. And we realized how much just time and labor it was going to be needed to complete this thing. It's just not going to happen. I mean, we're going to have one. Maybe, if we're lucky. So we sent the drawings out, far and wide, and the director of the parade shared them with her list. And, it was the early days of email, so we could email color images to lots of people. And we said, "this is what we're making. We need your help. Come this weekend." And we thought we might get five or ten people and we ended up with thirty or forty people who came in. And it was like, watching the whole thing happened in time lapse. You know, there was a lot of sewing involved that year and we had the caterpillar bodies on a pulley system so that you didn't have to sew on a ladder—you could just sew at the same height and you could pull the pulley and the whole thing would go up a stage and you'd sew the next rung, and sew the next one. And watching these things take shape, you know, five of them in the studio with all these people seated in chairs around them and just sewing and sewing and sewing—they just emerged. I mean, it was just like watching these trees grow out of the floor of the shop. And in one day we got, I think, two weeks of work done. And then we did it again two weeks after that, two weeks after that. I think we ended up hosting, like, four workshops, which we then dubbed "puppet raisings," because they literally were that—it was like a barn raising, but the puppets were actually going up towards the ceiling as they were being made. And so we realized at that point, this thing of people coming together, first of all, is fulfilling a need that people seem to have—to get away from spreadsheets and screens or whatever. I mean, this is before we even had iPhones.

AK: One of the things that happens with parades that have been around for a long time is that people remember the first parade and the second parade and maybe the third parade, and there is a kind of nostalgic—a bittersweet nostalgia, I should say—about where the parade has come since then. Twenty-five years along the Halloween Parade went from being 125 people meandering through Greenwich Village to being a massive thing on Sixth Avenue with over a million spectators and fifty thousand people in costume. So, for a lot of people, it's a little bit like the little puppy grows up into the big dog and you're like, "oh, my God, how are we going to feed this thing?" And it's not cute anymore. So, there was a lot of criticism of the parade. People saying, "Oh, it used to be this beautiful little family-friendly thing and now it's this massive corporate thing." Often people ascribe things to the parade that are not even true. Like, there isn't a wealth of corporate funding. We kind of wish there were, but there isn't. Because it's still a countercultural event and not everybody wants to have their name on it. A lot of people felt that the puppets themselves were a manifestation of its spectacle orientation, that it was no longer an intimate thing. Of course, giant puppets were part of the parade from year one. They were the only thing in the parade year one. So there was a lot of bitterness around the growth of the parade because it wasn't what people remembered that first few years, which I'm sure were magical. I wasn't there. I was six years old. So, we wanted to address that in the twenty-fifth anniversary by saying, "Look, things change. Events are organisms and organisms have a lifecycle. And sometimes they get so big that they can't sustain themselves anymore and they stop. And some times they plateau and become a mature version of themselves. And sometimes hey get small again or they break into many events like Burning Man has many small, Burning Mans that are happening these days." So we just want to acknowledge that, you know, performance. So we thought the best way to do that was through the metaphor of a cocoon, a larva becoming a cocoon, becoming a butterfly. So, we called it Metamorphosis. And we built five giant caterpillars, Luna Moth caterpillars, that were twenty-feet tall and lit from within glowing pink and green. And then at a certain moment in the performance, the idea was that their skins would drop off. It was like a lepidoteral striptease and their skins would come down and there would be these white, filmy moths underneath that suddenly would spread their wings and they had a twenty-, thirty-foot wingspan. And there were five of them in a circle. So, it was a massive circle of basically semi translucent material that then became a shadow stage for these human figures that then themselves spread wings and became sort of insect people that were flying around and taking flight. So this idea is that metamorphosis: yeah, it happens and it leads to new and wondrous things. They were beautiful caterpillars, but their lifecycle came to an end and they became something new and special. So the background of that is, that we started, you know, I started doing the drawings for it in June, maybe in May. We had kind of worked out a design plan. Sophia had done puppetry in her time at McGill and was interested in doing more. So we started working together on these things. But, what's interesting about that year is that not only were we working together, but it was the initiation of our whole public workshop process that became the kind of linchpin of our nonprofit work. So we worked all the way through to the end of August, mid-August, and we were looking at what we had accomplished over basically eight weeks of hard work in the summer with a few volunteers coming in now and then, but mostly just us, and a few people who we hired to do some extra work. But basically at the end of all of that work, we had one prototype that wasn't even really complete. And we realized how much just time and labor it was going to be needed to complete this thing. It's just not going to happen. I mean, we're going to have one. Maybe, if we're lucky. So we sent the drawings out, far and wide, and the director of the parade shared them with her list. And, it was the early days of email, so we could email color images to lots of people. And we said, "this is what we're making. We need your help. Come this weekend." And we thought we might get five or ten people and we ended up with thirty or forty people who came in. And it was like, watching the whole thing happened in time lapse. You know, there was a lot of sewing involved that year and we had the caterpillar bodies on a pulley system so that you didn't have to sew on a ladder—you could just sew at the same height and you could pull the pulley and the whole thing would go up a stage and you'd sew the next rung, and sew the next one. And watching these things take shape, you know, five of them in the studio with all these people seated in chairs around them and just sewing and sewing and sewing—they just emerged. I mean, it was just like watching these trees grow out of the floor of the shop. And in one day we got, I think, two weeks of work done. And then we did it again two weeks after that, two weeks after that. I think we ended up hosting, like, four workshops, which we then dubbed "puppet raisings," because they literally were that—it was like a barn raising, but the puppets were actually going up towards the ceiling as they were being made. And so we realized at that point, this thing of people coming together, first of all, is fulfilling a need that people seem to have—to get away from spreadsheets and screens or whatever. I mean, this is before we even had iPhones.

LD: And they were all volunteers?

AK: All volunteers. You know, not only was it fulfilling a need for them, but it was giving us a whole new way of designing large scale work on a limited budget. You know, if we had hired a scene shop to do exactly the same work we did, it would have been hundreds of thousands of dollars of expensive skilled labor. And whereas the people who were doing the sewing, some of them were very skilled costumers and the quality of work was just as good. So, we realized it's like designing multiples not only as an end result is desirable for parade art, but it's also desirable as a thing that you can do efficiently through the process of volunteer-based building. So that, if you're doing twenty completely different puppets, everybody has to learn twenty completely different processes. But if you're going to make a group of five, ten, twenty or a hundred things, that lends itself to that whole workday process. So over time, we've gotten better at tuning that building process in a way that's very—it's not quite Henry Ford-esque, but it has this sense of people find their way into the assembly line and they do one thing. You don't give somebody a start to finish project. You give them a satisfying but relatively limited component of it. And they pass it on to the next person. And at the end of the day, you know, somebody who's making eight man fingers or something like that, whose only job was to cut bamboo into three different lengths, drill holes in the end and stick a piece of wire in them, sees those hands actually animated and moving and come to life. And so that's really fun: to see what the end result is when it comes out the far end of the factory that you've actually, with the help of twenty or thirty other people, made this this thing happen.

SM: Yeah, I think it took me a good number of years to really feel comfortable with the fact that people were not coming solely because they felt sorry for us that we were not going to make our deadline. There was this perfect exchange of, we need help and we are offering people an opportunity to come to a beautiful place and be in a social situation, which is not just them sitting around a table, papier mâché-ing or sewing or whatever it is. They are a part of a social context that is easy because everyone has a thing to do and there's no pressure, but also, an artistic context that some people, who think of themselves as artists or define themselves as non-artists, both can come together and it's part of a larger collective performance. And the person cutting the bamboo for the hands can feel just as—like that is just as important a job as the final painting. They're all necessary. Just this idea of collective making and is really important for people. And it was not something that I had ever thought of before specifically. I don't think either of us went into this with a sense of, we need to make social art. It really was out of necessity. But, having established this way of working, it created the situation where at first it was only the Halloween Parade, and then, later on with all these other events that we do, there is this sense of, especially with annual events, there is a sense of, "It's that time of year again and we're all coming together to do this thing." And some people are new each year and some people are returning. But there's that sense of, "we are an ensemble. We are a collective working together." Coming into this experience from a theater background, there was all of this pressure towards opening night—the sense of the unveiling. In a way, opening night, meaning Halloween night, was like, "Well, we've all been working together in a way." The first workday, the first puppet raising is more of an opening night for us than the performance, because it is the unveiling of the idea and because physically there's nothing there yet. It's just so nice to go into that process with hundreds of people with you, whether they are physically with you on the night of Halloween or not, but have been helping make it and are invested in the project. And that translates to other projects that may be annual events. Or sometimes there are new projects, but just people are like, "we took our time. We took care and time and we invested it and we thought this was a good idea. We thought we would jump in."

LD: Sophia, you mentioned your theater background and Alex had talked about you doing some puppetry work at McGill. Can you talk a little bit more about that?

SM: Yes, I did actually do some puppetry work at McGill. My plan was to become an architect, but I didn't want to do study architecture as an undergrad, so I did an art history program at McGill, which I loved. Because I always had drawn and painted and made stuff, I decided not to go to art school and McGill had no art program, a friend of mine at some point asked if I could design a set for a small play. It was very easy. It was very little. Theater was not something I did, particularly, but I realized that I was really interested in set design, and in a way it sort of satisfied a lot of what I was interested in in architecture, in terms of creating space. But it was more immediate and I loved the collaboration that theater offers. I was the set designer and then there's a lighting designer and the director and the actors and everyone was coming at this same piece from different perspectives. That was a real eye opener for me and I changed course and said, "Okay, forget architecture, I'm going to be a set designer." And then, at the end of my last year, one of the larger performances was a South African play called Tooth and Nail by the Junction Avenue Theater Company, and it involved five large-scale puppets that interacted with the actors and I didn't want to do it. I had to choose between that and something that I thought would be better for my CV and I was going to graduate and I thought that was the better plan. It was a more serious thing. But the director had seen other work that I had been doing on in smaller productions on campus, and I'm glad she insisted because it was this great learning experience for me. Again, like a couple of years after my first introduction to set design where I realized, "Oh, I love creating space," but, I had forgotten about movement. I'd forgotten about the idea. That same thing that I loved about theater—in terms of collaborating with the other perspectives—what I loved about working on that performance was that I was creating puppets that were going to interact with actors. It was not a puppet play—it was an exchange of these different species. And that really opened up a whole new way of thinking, and it was from that that I then went and started working with Alex on Metamorphosis, building these Luna moths. And to me, that step, of taking a performance outside of the theater and onto the street, was a natural one—that sense that we're going to still design something, but we're going to put it out into the public realm, made a lot of sense. In many ways during those first few years working as we were, we worked on the Halloween Parade and we started developing projects on our own, where there was no history of processions or parades. Seeding our own processions, as it were. Whether it's the beginning of a procession that may become an annual event or like the Halloween Parade, which had been going on for twenty-five years at that point and had grown to be this very large event. What an effect an ephemeral performance in public space—which is what a procession is—what kind of an effect it has on public space. In many ways I realized I actually haven't strayed that far from architecture. I am actually still satisfying this idea, that is maybe more urban design than architecture. But just the anticipation of a public event like the Halloween Parade and the residue, the memory, of it that people have can really affect their sense of local public space. Whether it's urban space or whether it's like the project that we do in the Alps, in Italy, where it's a teeny village and we go through the fields to the church and back. But especially when it's an annual event, it really does affect people's memory of a street that they walk down every day and it changes their perception of that space. And it also allows them to take ownership of that space, if they're contributing their work, if they're contributing their performance, if they're contributing, in many cases, their stories or their images to processions that we are creating, where they get to make a change.

AK: There was a theorist at MIT in the urban planning program there, twenty or thirty years ago, whose name is J. Mark Schuster. He had this great term for what Sophia is describing, which is "signature ephemera." He basically said that urban designers should be thinking about the presence of ritual performance as a key component of how they think about making an urban space or redesigning an urban space. That if you don't cultivate it or allow fertile ground for these temporary performative rituals—and they might be artistic or they might even be like, he uses the swan boats in Boston Common as an example, or bourse or markets or bazaars or whatever—but, he says that if there isn't some acknowledgment that things that come and go and leave an imprint is important in urban space, you'll end up with this soulless public space that is nothing but space and there's no accommodation for time. So, I find that really inspiring that an urban theorist was seeing this work in the same terms.

SM: Yeah, that's definitely it. I mean, as a background to the work that we're doing, I think that's something that we're both interested in. In terms of thinking more about how the work that we do—and Carnival and public performances in general—affects space and how can we keep that in mind in our work.

LD: The same question for Alex. How did you first get involved with this medium before you and Sophia started working together?

AK: Yeah, I feel like there's three stories that sort of intertwine in a non-linear way. So, it definitely wasn't a planned career path. I did fine art, or, as they called it in the program where I was studying, visual art/visual environmental studies, when I was in college.

LD: And where was that?

AK: At Harvard. There was a program there that was really based on the Bauhaus model, where they weren't trying to generate a bunch of studio artists who would then try to get their work into galleries, but they wanted you to see more broadly in terms of visual culture. So, there were people designing fonts. There were people designing playgrounds for blind children. There were people just writing theory. It was that it was a much more broad-based kind of approach to how visual things affect us in society. But my primary focus was sculpture and painting and that evolved into room-sized installations—what we would call today, immersive experiences. And then within those immersive experiences, there were puppetry components—motors and things that were driven by servos and things like that. So, I would open a door in a wardrobe kind of structure and people would pass through the wardrobe into this fantasy realm and then be ejected through the back end of it at the end. And as I was working on that, I was thinking, "what I'm really trying to do here is change the point of encounter between the viewer and the artwork." That, really, it was a collection of painted works and kinetic sculptures, but I didn't want them to be on white pedestals in a white box. I didn't want people to have the luxury of clinical detachment from the work. I wanted them to feel like they were in a place and more experiencing a posture of discovery than presentation. So how do you engineer that? Well, you can do that through installation work, but I was thinking to myself as I was doing the work that there are cultures where that's a given: where the way in which people interact with their visual culture is much more intimate, much more personal, much more embodied with some sense of religion or ritual practice or things like that. So after I graduated, I got this grant to go to Nepal and I lived there for a year. I went to festivals and I painted thangkas, traditional Buddhist scrolls, which are very ritually determined. You know, you have to put this icon in this spot and this thing has to be this color and hand gestures and facial expressions are all predetermined. But I was really interested in how at the end of that practice these things get consecrated and then they get used in religious practice. I wouldn't say people worship them—I think that's a misunderstanding of Buddhist practice, but, they become condensation points for practice. They become a place which gives you a visualization that helps you go further in your practice. And I was like, that's so amazing. Nobody is looking at these things and saying, "I would have done it differently. I don't really like the color or the design. Man, yeah, I could use that maybe above the mantelpiece." That would be unthinkable. You know, they were invested presences for the people who use them. And then in the festivals it was the same thing. They were building huge effigies. I watched people build giant Buddhas out of butter and flour and then throw them off cliffs, which in the Himalayas there's some pretty serious cliffs, things off of. [laughs.] In the process of having a procession with sound and all this stuff. So, you know, that all got into my head in terms of like this is an entirely different way of engaging artistic works. But I didn't want to come back to the US and become a Buddhist monk and do Buddhist processions. I wasn't particularly into adopting or appropriating Tibetan culture as what I needed to do. But I thought there must be things I can draw from this. And at the same time, I needed to make a living. So I ended up finding myself doing a lot of theatrical work.

LD: At around what time was this?

AK: It was the early nineties. So I was in Nepal from '89 to '90 and then really was sort of back on my feet and looking for something to do in '91. So one of the first things that happened was I came back and I was looking for internships and one of my heroes in the world of avant-garde art is Meredith Monk. And I had heard that through the Department of Cultural Affairs, "Oh, she's always looking for interns," because she's doing these huge spectacle kind of things. So I called up her foundation and they said, "Well, there are these artists who are building some work for her. You should contact them." And I contacted them. And it was this weird roundabout thing that it turned out that they were building, at that time, puppets for the Village Halloween Parade. Oh, great, well, "Where does that happen?" "Well, that happens at a place in upstate New York." And I said, "Well where's that? It's in Red Hook, New York." Well, that's where I'm from. That's where I grew up. And it turned out that they were building the Halloween Parade at Rokeby, where we are now. And at the same time, Sophia's uncle [Richard "Ricky" Aldrich] had been asking me, "What are you going to do now that you're back from Nepal?" And I was like, "I don't know. I just want to do something creative." And he said, "You should talk to these people and making giant penguins over at Jeanne's house [Jeanne Fleming]." So I went over and they were the same people who were the designers for Meredith Monk who were now doing the parade. And I was just like, "I'm working for you!" So I started apprenticing with them in 1991, cutting out metal fish on a band saw and creating giant foam, rubber, octopuses and squids and whatever else they wanted me to do. I had some basic skills—not a lot of theater experience at that point, but through them, I ended up doing more commissions for Meredith Monk and doing larger-scale theater works in New York and then eventually ended up becoming the technical director at The Kitchen, which had a long relationship with Meredith. So it was this whole natural kind of folding into the downtown art scene. The Kitchen, for me, was really—like, that was grad school for me. That was before I actually went to grad school. That was like three years in the downtown art scene. Anything could happen in that space. I mean, The Kitchen, for those who don't know, it is like this super experimental, or, at least it was back then, giant black box, twenty-two foot high grid in an old ice house and everybody from Laurie Anderson to La Fura del Baus to Diamanda Galas, Robert Wilson, Laurie Anderson—everybody came through. The Talking Heads, especially in the late seventies and early eighties. And in the ninities, they were getting into doing stuff with the rave/new DJ-as-art scene. There were these amazing full-building installations that were going up. So, I was in heaven. I didn't know a whole lot about the downtown art scene. And just every show that came in taught me new skills. And as the technical director, I was responsible for implementing a lot of things that I had no idea how to do. But little by little, I got to know the artists and their work and their practices and how they functioned. There was a lot of visual theater—a lot of object-based theater that was borderline puppetry, but was also more like what Pina Bausch does, sort of Tanztheater. So, I just absorbed all of this stuff and it just made me want to do something that was theatrical, that was creating these strangely engineered encounters between art object and audience. I had the ritual theater thing coming from Nepal. I had this sort of stagecraft and avant-garde theater that was coming out of The Kitchen, and meanwhile, I had been continuing to paint and draw, and I'd been getting very into printmaking. So I ended up going to San Francisco and getting my MFA in printmaking [at San Francisco Art Institute] and again, doing this sort of installation work there, where the prints were incorporated into this imaginary museum that you had to wander through and open drawers with strange sounds and light and mobile objects and projections. So about then is when I got a call from Jeanne to come and design it.

AK: It was the early nineties. So I was in Nepal from '89 to '90 and then really was sort of back on my feet and looking for something to do in '91. So one of the first things that happened was I came back and I was looking for internships and one of my heroes in the world of avant-garde art is Meredith Monk. And I had heard that through the Department of Cultural Affairs, "Oh, she's always looking for interns," because she's doing these huge spectacle kind of things. So I called up her foundation and they said, "Well, there are these artists who are building some work for her. You should contact them." And I contacted them. And it was this weird roundabout thing that it turned out that they were building, at that time, puppets for the Village Halloween Parade. Oh, great, well, "Where does that happen?" "Well, that happens at a place in upstate New York." And I said, "Well where's that? It's in Red Hook, New York." Well, that's where I'm from. That's where I grew up. And it turned out that they were building the Halloween Parade at Rokeby, where we are now. And at the same time, Sophia's uncle [Richard "Ricky" Aldrich] had been asking me, "What are you going to do now that you're back from Nepal?" And I was like, "I don't know. I just want to do something creative." And he said, "You should talk to these people and making giant penguins over at Jeanne's house [Jeanne Fleming]." So I went over and they were the same people who were the designers for Meredith Monk who were now doing the parade. And I was just like, "I'm working for you!" So I started apprenticing with them in 1991, cutting out metal fish on a band saw and creating giant foam, rubber, octopuses and squids and whatever else they wanted me to do. I had some basic skills—not a lot of theater experience at that point, but through them, I ended up doing more commissions for Meredith Monk and doing larger-scale theater works in New York and then eventually ended up becoming the technical director at The Kitchen, which had a long relationship with Meredith. So it was this whole natural kind of folding into the downtown art scene. The Kitchen, for me, was really—like, that was grad school for me. That was before I actually went to grad school. That was like three years in the downtown art scene. Anything could happen in that space. I mean, The Kitchen, for those who don't know, it is like this super experimental, or, at least it was back then, giant black box, twenty-two foot high grid in an old ice house and everybody from Laurie Anderson to La Fura del Baus to Diamanda Galas, Robert Wilson, Laurie Anderson—everybody came through. The Talking Heads, especially in the late seventies and early eighties. And in the ninities, they were getting into doing stuff with the rave/new DJ-as-art scene. There were these amazing full-building installations that were going up. So, I was in heaven. I didn't know a whole lot about the downtown art scene. And just every show that came in taught me new skills. And as the technical director, I was responsible for implementing a lot of things that I had no idea how to do. But little by little, I got to know the artists and their work and their practices and how they functioned. There was a lot of visual theater—a lot of object-based theater that was borderline puppetry, but was also more like what Pina Bausch does, sort of Tanztheater. So, I just absorbed all of this stuff and it just made me want to do something that was theatrical, that was creating these strangely engineered encounters between art object and audience. I had the ritual theater thing coming from Nepal. I had this sort of stagecraft and avant-garde theater that was coming out of The Kitchen, and meanwhile, I had been continuing to paint and draw, and I'd been getting very into printmaking. So I ended up going to San Francisco and getting my MFA in printmaking [at San Francisco Art Institute] and again, doing this sort of installation work there, where the prints were incorporated into this imaginary museum that you had to wander through and open drawers with strange sounds and light and mobile objects and projections. So about then is when I got a call from Jeanne to come and design it.

LD: And this was Jeanne—?

AK: Jeanne Fleming, director of the Halloween Parade, to design the twenty-fifth anniversary. So that was 1998. I took a semester off of graduate school, you know, hooked up with Sophia as a partner, and we design that twenty-fifth anniversary parade. And then it got complicated because I got a job teaching printmaking in Maine [Maine College of Art] and the printmaking—you know, it's funny. People are like, "Oh, that's completely different from doing giant puppet parades in the street." I was kind of like, "Well, no, not so much." I mean, Bread and Puppet, for example, is very renowned for their street theater, a huge component of the director's, Peter Schumann, work is his work in printmaking, because for him, it's multiples, it's variations on a theme, very much our workshop process. It's a very public art form because if you make one hundred of something, it means you can sell it for cheap or give it away. So often in our work, even today, there's a component of gifting. In this previous Halloween Parade, we were giving seed packets out as part of our wilderness ethos that we were creating around the wild things that we had made. So, even that was a component of stamping, dissemination, printing. So that also became a component of the work. Sometime around 2006, I'd been teaching full time and coming back to Rokeby to design with Sophia the Halloween Parades for these big weekend workshops that we did. And it was starting to feel like quite a stretch to be teaching a full load, to be a department chair and to be designing the Halloween Parade all through October. I was sort of feeling like there were two trains on slightly diverging tracks. And sooner or later, you're going to have to decide which one you're on. I applied for a Fulbright to go to Trinidad and got the Fulbright. So Sophia and I packed up and moved to Trinidad for six months to just be working on Carnival there. I took a leave of absence from teaching and then extended that leave of absence when we came back and did a few projects. Not that much at that time. We were not a nonprofit. We were not getting that many jobs, but it was sort of like, well, people do seem sort of interested in this kind of work. And then eventually, after I'd taken two years of leave of absence, the dean was sort of like, are you actually going to come back or is this just like an infinite leave of absence? The implication being, like, you know, pick your train—it's time. So, not without some agonizing, we decided to jettison the stable, retirement fund, health care-endowed teaching job and go into creating our own nonprofit, which we incorporated in 2005. The 501(c)(3) was established in 2008. And since then, that has been our full time job. When people ask, "How did you get into this and why?," I can tell you the narrative. I can't really answer the question, but those are the threads.

SM: And again, going back—sorry, I cut you off.

AK: Well, I was just going to add that, in the end, going back to that Nepal thing—that idea of engineering, fertile and unorthodox encounters between the art and the viewer—that's still there. I mean, that's very much a part of every time a puppet reaches its hand over the barricades to touch a spectator, every time we create an immersive environment that people can wander through and have that posture of discovery rather than presentation. I think that's still manifest. So although we're not doing Buddhist processions, I feel like that was that was seminal in a way of restructuring time and space and how we do procession.

SM: I can't remember what I was going to say.

LD: Well, I wanted to track back a bit because I don't think I realized that the Halloween Parade had had such a long legacy at Rokeby before your work together. And so, Sophia, I was wondering if you could talk a little bit about your relationship with Rokeby.

SM: Yeah. So, I guess, for the record, Rokeby is my family's house and estate, which has been in the family—the house was built in 1815, but the property has been in the family—I'm the eleventh generation. Our daughter is the twelfth generation of kids to live at Rokeby as direct lineage, which is rare, particularly in this country. So, it's this very interesting place and one of the many ways that we keep the property going is that a lot of the—not the main house, but a lot of the buildings around the farm and the property are rented to tenants and some are people who stay for a few years and go. And then we have a few tenants who've been here for a very long time. And, Jeanne Fleming, the director of the Halloween Parade, has been here since the seventies and even before she started working with Ralph Lee on the Halloween Parade. When she did become the director of the Halloween Parade, she invited Debbie Lee Cohen and Mark and Maya to come and work out of her house and to reintroduce that element of puppetry or—not reintroduce it, but keep it going after Ralph Lee's tenure. So, there was a history of puppetry relating to Halloween Parade happening and puppets getting built at Rokeby. The way that they built the puppets for the most part was not in public workshops. It was a smaller group of people working really hard for the month of October. But, the parade was also a smaller event—significantly smaller than it is now. So my aunt, Ania Aldrich, was part of that—a lot of the earlier puppets from the eighties she worked on and a lot of them are her—maybe not the overall design—but her painting and her artistry. And so it was funny because when I was at McGill and the director asked me to design these puppets for Tooth and Nail because the other components of design were taken on by faculty, but none of them wanted to have anything to do with puppetry—first of all, I was trying to get out of it, but also, I just thought it was really funny because I was like, how did you know this was my family business? [laughs.] I can't escape! And then when I did finally say yes, even though I ventured into this project, really having never done anything like it and I was trying to figure things out, I had three other students working with me and I was a half hour ahead of them in terms of figuring things out, but I did have a few people that I knew through the Halloween Parade, one of them being Alex, who in the summer I had sort of interviewed. "Okay, just tell me stuff!" I don't know. I remember this early conversation that we had where I was taking notes, I think, "Okay, you know, like a backpack with a pole coming out. Oh, that's brilliant. Okay." You know, like the sort of things that I might have figured out and some of them probably not. But it was just helpful to know that there were a few people out there who could help me if I really wanted.

AK: Did you talk to Basil at that point?

SM: [to AK] I talked to you and I talked to Basil Twist, who is a puppeteer in New York City. I mean, I remember going to Basil's studio and just looking through all of his—he had all these magazines and I was just so thirsty for that stuff because I was like, "Okay, I've accepted this commission and I had never paid any attention to puppetry specifically, and I had a sense for what was going on in the Halloween Parade, somewhat, but only peripherally, tangentially." So it was this interesting connection. It was just nice to know that there was a community of people out there. But then within that, I had to invent things on my own for this purpose, which was different—which was a staged performance.

LD: So along those same lines, you've mentioned the precedent of Ralph Lee's Giant Puppets, which premiered for the Halloween Parade in 1973. Can you talk a bit more about your relationship with his work, or any other inspirations?

SM: Well, I would say Ralph is an absolute inspiration. He does really amazing work. He's just a great person. We only met him about ten years ago, I think. We had met him—

AK: We encountered him at the Jim Henson Festival at the Public Theater in 2000 [Henson International Festival of Puppet Theatre, Joseph Papp Public Theatre, New York]. I guess we brought the moths [from Metamorphosis] down. But that was like a glancing moment.

SM: Yeah. We didn't have any interaction with him particularly. But then we had a common friend who, about ten years ago said you all must meet and Ralph and his wife Casey came up for lunch and we just had this lovely day. And then subsequently, we saw them in the city and have had a few—it was just nice to meet this person whose work we had admired and whose work in some way we had inherited. You know, we've inherited some of his legacy. And just to realize what a what an inspiring person he was as well as his work.

AK: A lot of people know Bread and Puppet primarily from their work in New York in the sixties and in the pageants that they did up in Vermont. And so when you think about puppets on the street, you think of Bread and Puppet as an obvious place to go to. But, what inspired me in Ralph's work was that what he was bringing out onto the street on Halloween night and it was '74, I think, was the first parade, was not specifically in the context of a political protest or a polemic or a message that needed to be translated into puppetry and brought to the people. That has always been an important focus of Bread and Puppet, that they are fundamentally a politically-oriented organization. And so a lot of their puppetry is about allegory for capitalism or the evils of environmental destruction or things like that. Ralph—I think his work fit so well for Halloween because he's much more open about what these things might mean. There's a lot more room for the viewer to find their way into them and say, you know, I don't know exactly what Ralph's mythology is for these sweeper figures that lead the parade, but there is something amazing about that simple gesture of these sad faces and these brooms that are sweeping the street clean. You know, people see politics in it, but they also see mythology and they see just a beautiful choreographic gesture. And so for me, just the playfulness of Ralph's work and yet the fact that it can be playful on an epic scale—that he is working large, that there are many people carrying one thing. He still has puppets that come to St. John the Divine every year and they do this descent of the devils through the church. Just the fact that St. John allows there to be this infusion of devils is a testament to Ralph's work, because they're not malevolent. There's this wonderful curiosity and playfulness to them that on this one night we're allowing them to explore the earthly realm. And so for me, that they're much more rounded characters has led me when we've designed stuff for the Halloween Parade, to be wary of too much overt allegory. Something that people often ask us in the work that we do this like, "Is everybody going to get all of the references that you've put in there?" And I say, "Well, like any artist, no. Any given single audience member is not going to see this as an encoded message that you then decode and get the message from. We're not about carrying essentially signage in puppet form. What we want to do is have people find aspects of their own narrative, their own associations, their own preconceptions, and then somehow lock onto them with the puppets that they see in the parade." So, Ralph's work, what we've seen of it very much, is very much open to that in the same way that our work is open to that. You know, I don't know what more to say about it—